Answers supported with vowel and consonant acoustics.

[Image from https://waygaze.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/7decf-vocal-tract.gif]

In this essay I will be outlining the source-filter model’s affect on the production of speech sounds and their acoustic properties. I begin by introducing the source-filter model and discuss its various sources including Periodic Excitation and Constrictions (specifically, Turbulent Excitation and Transient Excitation). I then describe the various filters of the vocal tract including the role of damping and vocal tract shape on filtering properties, discussing their affect on vowel and consonant acoustics. Finally, I discuss the affects of lip rounding and the nasal cavity on speech sound acoustics

1. Source Filter Theory

1.1. What is Source Filter Theory?

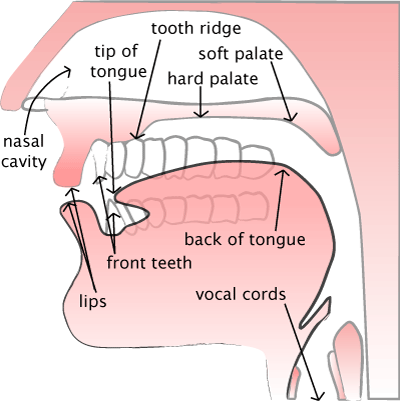

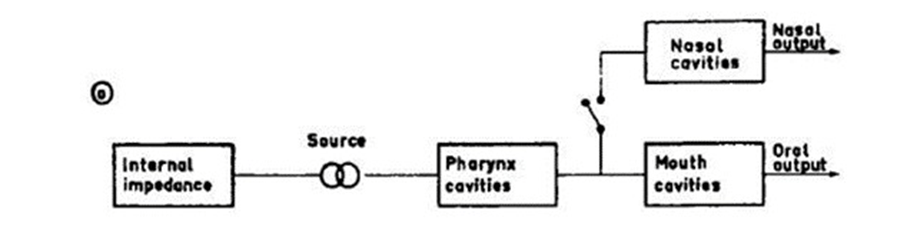

Source filter theory describes the acoustic properties of sounds in terms of source and filter characteristics (Reetz & Jongman, 2008). The representation of the source-filter model in Figure 1, presents the pharyngeal, oral and nasal cavities of the vocal tract as filtering units of the glottis source signal (Reetz & Jongman, 2008; Tatham & Morton, 2011). Filtering of the complex wave of the source signal results in a broad range of output frequencies which we perceive as speech sounds (Reetz & Jongman, 2008; Tatham & Morton, 2011). Filtering qualities of the vocal tract are dependent on its shape and subsequent resonant and damping properties (Reetz & Jongman, 2008).

1.2 Source

In most speech sounds, energy for source signals is acquired from the lungs and converted into audible frequencies of 20Hz-20,000Hz (Reetz & Jongman, 2008; Sondhi & Schroeter, 1999). Sources can either result in periodic, turbulent, or transient excitation of source energy or combinations of these excitations in the case of sounds with multiple sources (Sondhi & Schroeter, 1999). Sources for speech sounds are the vocal folds, vocal tract constrictions, and tongue motions (such as trills) (Reetz & Jongman, 2008; Sondhi & Schroeter, 1999).

1.2.1. Periodic Excitation. The vocal folds produce the main source of periodic excitation (regular fluctuations of air pressure) which is the source of all voiced sounds (Reetz & Jongman, 2008; Sondhi & Schroeter, 1999). Vocal folds are made to vibrate when adducted and a pulmonic egressive airstream builds up behind them; this pressure results in the Bernoulli effect and a resulting quasi-periodic source signal (Reetz & Jongman, 2008; Sondhi & Schroeter, 1999). This periodic excitation is visible as vertical striations in spectrograms (Ladefoged, 2014).

Due to the complex oscillations of the vocal folds, this periodic signal is made up of a complex wave that carries frequencies far above the vocal fold’s fundamental frequency (Reetz & Jongman, 2008). Changes in the elasticity, dimensions and tensions of the vocal folds alter their vibratory properties and thus their resonating frequencies (Franklin, Muir, Wilcocks & Yates, 2010; Reetz & Jongman, 2008). This complexity in vocal fold movement, accompanied by vocal tract filters, enables the production of a broad range of sounds (Reetz & Jongman, 2008).

1.2.2. Constriction. Another source is caused by constrictions between articulators; the place of constriction can occur at the lips, between the lips or tongue and another articulator, and at the glottis (Reetz & Jongman, 2008). Constrictions can be defined in terms of the articulators involved (place and tongue frontness) and degree of constriction (manner and tongue height) (Tatham & Morton, 2011). They can result in turbulent or transient excitation which relates to the production of fricatives and plosives (Sondhi & Schroeter, 1999).

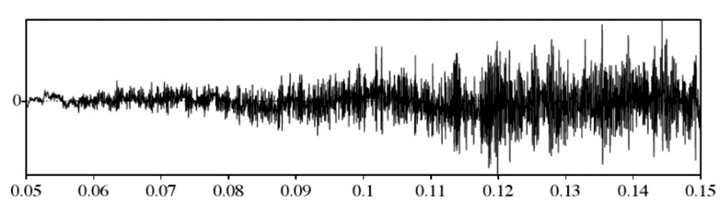

1.2.2.1 Turbulent Excitation. Turbulent airflow occurs in most voiceless sounds and is formed when air is forced through a narrow channel between articulators, resulting in random fluctuations in air pressure (aperiodic waves) (Sondhi & Schroeter, 1999). Turbulent excitation can occur at constrictions between the glottis and the lips and at the glottis (Sondhi & Schroeter, 1999). The vocal folds can serve as articulators (in addition to their ability to vibrate) creating a narrow constriction and resulting in glottal fricatives (Reetz & Jongman, 2008). In Figure 2, this turbulent airflow is shown in the aperiodic wave.

1.2.2.2. Transient Excitation. Transient excitation occurs when air pressure builds up behind a closure (constriction) and is suddenly released and not sustained or repeated (Johnson, 2012; Sondhi & Schroeter, 1999). Such constrictions occur in the cases of stops (plosives) and clicks (Johnson, 2012). The acoustic properties of transients can be seen in their characteristic segments: the closure, hold and release phases (Ogden, 2009).

During the closure phase, the vocal tract’s shape is changed when a complete closure is formed by two articulators moving together (Ogden, 2009). Consequently, natural resonances of the vocal tract change, and formants (F) of the output wave move closer together (transition) (Ogden, 2009).

The hold phase results in a gap or a voice bar in spectrograms due to the complete closure of the vocal tract (Reetz & Jongman, 2008). A gap indicates no vocal fold vibration and thus no energy from an output signal, this is the acoustic property of voiceless stops (Johnson, 2012; Reetz & Jongman, 2008). Alternatively, a voice bar contains low frequency periodic energy, characteristic of voiced stops, which usually dissipates over time as airflow is discontinued, (Johnson, 2012; Reetz & Jongman, 2008). In Figure 3, the voiceless alveolar [t] shows a lack of energy in the hold phase whilst the voiced alveolar [d] contains a voice bar, which fades near the end of the closure (Johnson, 2012).

The release phase involves a release of pressurised air, when articulators separate, producing a burst of noise for voiceless stops or a sharp beginning of formant structure for voiced stops (Ogden, 2009; Reetz & Jongman, 2008). Voice onset time (VOT) is the duration between the onset of voicing and the release; longer VOTs are typical of English voiceless plosives (Ogden, 2009) This characteristic of VOT is shown in Figure 3, where the voiced alveolar plosive [d] has a shorter VOT than for the voiceless alveolar plosive [t] (Reetz & Jongman, 2008).

1.2.3. Other Sources. Another source of sound is tongue motion such as trills, taps and flaps (Ladefoged, 2014; Reetz & Jongman, 2008). In a trill, the tongue touches the mouth’s roof in a fast repetitive motion due to aerodynamic forces (Ladefoged, 2014). Alternatively, a tap and flap are produced by a rapid touching of articulators; taps are articulated in the alveolar and dental area by the tongue tip whilst a flap is articulated with the tongue tip curled up before the postalveolar area is struck as the togue lowers (Ladefoged, 2014).

1.3. Vocal Tract Filters

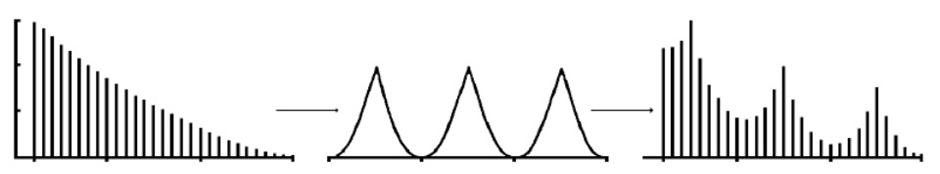

An acoustic filter passes or attenuates components of sound waves at specific frequencies, similar to how light is filtered through coloured glass (Johnson, 2012; Reetz & Jongman, 2008). For speech production, source signals are filtered via the vocal tract (due to its resonating and dampening qualities) into a range of perceivable sounds (Reetz & Jongman, 2008). Resonance frequencies and filtering properties of the vocal tract are dependent on its shape (Franklin, Muir, Wilcocks & Yates, 2010). In Figure 4 below, filtering is visualised through the modulation of the source signal (glottis) as it travels through the vocal tract; its output can be seen with peaks of energy (formants) which correspond to the resonating frequencies of the vocal tract due to its shape at that time (Tatham & Morton, 2011).

The jaw, lips, and tongue can change the vocal tract’s shape and thus determines its frequency response (Sondhi & Schroeter, 1999). Formant frequencies are regions of energy concentration around a frequency in the output signal (Sondhi & Schroeter, 1999) Vowels can be distinguished from one another through the figurations of these formants (Sondhi & Schroeter, 1999). These formants are not as prominent for obstruents, however, areas of concentrated energy in broad frequency regions characterise them (Sondhi & Schroeter, 1999).

1.3.1. Damping. Energy lost in vibratory systems is defined as damping and in the vocal tract is attributed to friction, absorption, and radiation (Hixon, Weismer & Hoit, 2018; Reetz & Jongman, 2008). Energy is dissipated through heat generation when air molecules produce friction by rubbing against the vocal tract walls and one another. Energy is also lost when vibratory energy transfers to the vocal tract tissues (absorption) and when lost out the mouth and nose (radiation) (Hixon, Weismer & Hoit, 2018). All frequencies passing through the vocal tract are dampened (Reetz & Jongman, 2008).

1.3.2. Vocal tract length. The jaw, lips, and tongue can alter vocal tract shape and thus determine the frequency response of the vocal tract (Sondhi & Schroeter, 1999). Vowels can be distinguished from one another through the figurations of these formants (Sondhi & Schroeter, 1999). These formants are not as prominent for obstruents, however, areas of concentrated energy in broad frequency regions characterise them (Sondhi & Schroeter, 1999).

As well as being a cause of constriction and a producer of turbulent and transient excitation, the tongue functions as a way of altering the shape of the vocal tract (Gick, Wilson & Derrick, 2013). The tongue height and backness can change through the use of the tongue’s extrinsic muscles, tongue height is also affected by the jaw’s up and down motion as the tongue (Gick, Wilson & Derrick, 2013).

1.3.3. Fricative Vocal Tract Lengths. A shorter vocal tract length results in higher frequencies in the output signal (Johnson, 2012). Tight constrictions (like in fricatives) create a front and back cavity due to weak acoustic interactions between them; therefore, the front cavity acts as the filter for constricted sounds (Johnson, 2012). Accordingly, higher resonant frequencies occur in fricative constrictions the closer they are to the lips as vocal tract length determining resonance becomes shorter (Johnson, 2012). Therefore, bilabial fricatives such as [f] have higher resonant frequencies than pharyngeal fricatives such as [ħ] (Johnson, 2012).

The amplitude of fricatives is also affected by vocal tract length in front of the constriction, with amplitude decreasing with longer lengths (Johnson, 2012). Amplitude is also affected by the degree of constriction, with narrower channels resulting in higher amplitudes (Johnson, 2012).

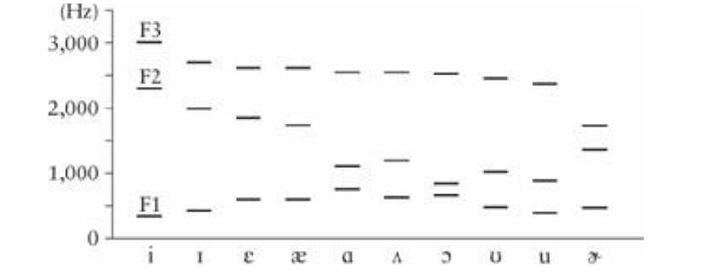

1.3.4. Vowel Vocal Tract Shapes. Vowels have a relatively high intensity (loudness) as the vocal tract is largely open and the airstream largely unimpeded. Vowel source signals usually have periodic excitation of the vocal folds (voicing) (Reetz & Jongman, 2008; Hixon, Weismer & Hoit, 2018). Acoustic cues to vowel quality are provided in F1-F3 whilst the formants in the higher frequencies vary more in speaker identity than in vowel quality (Reetz & Jongman, 2008; Sondhi & Schroeter, 1999). These formants provide information about the height, backness, and rounding of a vowel (Reetz & Jongman, 2008).

Different shapes in the vocal tract result in characteristic vowel formant frequencies (Ladefoged, 2014). In general, F1 and F2 correspond to the shape of the tongue; F1 corresponds to tongue height whilst F2 is affected by backness and lip rounding (Ladefoged, 2001). Tongue backness is more accurately determined by the frequency difference between F1 and F2 (Ladefoged, 2001). As demonstrated in figure 5, the high front vowel [i] has a lower frequency F1 and a higher frequency F2 than the low back vowel [ɑ]. Moreover, F1 and F2 are closer together in [ɑ] than [i] which corresponds to the more open oral space caused by jaw lowering and resultant tongue lowering (Johnson, 2012; Gick et al, 2013).

American English produced by 50 male speakers’ (Johnson, 2012, p.245)

1.3.5. Lip rounding and Vocal Tract Shape. Lip rounding also changes vocal tract shape by increasing vocal tract length through protrusion and changes in lip area resulting in lower output signal frequencies (Fant, 1971; Reetz & Jongman, 2008). Resonant frequencies affected the most by the cavity behind the lips are most affected with a decrease of all in F1-F4 region (Fant, 1971).

As mentioned previously, F3 does not provide a cue to vowel quality in English, however, in other languages (like German, see Figure 6)it does (Johnson, 2012). This is displayed in the spectrogram of Figure 6, where the rounded high-front vowel [y] has an F3 closer to its F2 than the unrounded high front vowel [i]. In addition, the general lowering of all the frequencies can be seen in the spectrogram for [y] in comparison to its unrounded counterpart.

Jongman, 2008, p.244)

1.3.6. Nasal Cavity. As seen in Figure 1, the nasal cavity functions as a vocal tract filter when air flows through the open velopharyngeal (Tatham & Morton, 2011). When the nasal cavity is in use, the vocal tract must be thought of in a two-tubed model; the nasal cavity through to the glottis can be thought of as a closed-open tube whilst the oral cavity (second tube) is closed at its constriction and open at the uvular (Reetz & Jongman, 2008). Nasal sounds have characteristic acoustic properties including a low F1, formants with low amplitude, increased formant bandwidth, and the presence of anti-formants (Reetz & Jongman, 2008).

The interaction between the nasal and oral cavities results in characteristic antiformants (Reetz & Jongman, 2008; Sondhi & Schroeter, 1999). Resonance frequencies in the nasal cavity, similar to the oral cavity’s, are absorbed resulting in low-frequency points in the spectra (anti-formants) (Johnson, 2012). The place of articulation of nasal sounds determines frequencies of anti-formants; higher frequency anti-formants arise from articulation further back in the vocal tract whilst lower frequency anti-formants are a result of more forward articulations (Johnson, 2012). As shown in Figure 7 below, the antiformant in velar [ŋ] has a higher frequency range than the anti-formant in bilabial [m] (Johnson, 2012).

Due to the addition of the nasal cavity, the total cavity length of the vocal tract is longer when producing nasal sounds which result in the low F1 or ‘nasal formant’ (Reetz & Jongman, 2008). This is due to damping as the energy absorbed by the vocal tract cavity walls increases (Reetz & Jongman, 2008). Apart from the low F1 ‘nasal formant’, nasal sounds are similar to that of vowels in formant structure (Reetz & Jongman, 2008).

References

Fant, G. (1971). Acoustic theory of speech production : With calculations based on x-ray studies of russian articulations [Ebook]. Mouton: The Hague. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/lancaster/detail.action?docID=3044232.

Franklin, K., Muir, P., Wilcocks, L., & Yates, P. (2010). Introduction to Biological Physics For the Health and Life Sciences. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Gick, B., Wilson, I., & Derrick, D. (2013). Articulatory Phonetics [Ebook]. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/lancaster/detail.action?docID=1120664.

Hixon, T., Weismer, G., & Hoit, J. (2018). Preclinical Speech Science: Anatomy, Physiology,

Acoustics, and Perception [Ebook] (3rd ed.). San Diego: Plural Publishing, Incorporated. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/lancaster/detail.action?docID=5509496.

Johnson, K. (2012). Acoustic and Auditory Phonetics [Ebook] (3rd ed.). Chichester: John Wiley

& Sons, Incorporated. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/lancaster/detail.action?docID=698133.

Ladefoged, P. (2001). Chapter 8: Acoustic Phonetics. In: A Course in Phonetics [Ebook]. London: Harcourt.: Harcourt. Retrieved from https://modules.lancaster.ac.uk/course/view.php?id=34065

Ladefoged, P. (2014). A Course in phonetics [Ebook] (7th ed.). Cengage Learning. Retrieved from https://r4.vlereader.com/Reader?ean=9781473714342

Ogden, R. (2009). An Introduction to English Phonetics [Ebook]. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/lancaster/detail.action?docID=537027.

Reetz, H., & Jongman, A. (2008). Phonetics : Transcription, Production, Acoustics, and Perception [Ebook]. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/lancaster/detail.action?docID=819405.

Sondhi, M., & Schroeter, J. (1999). Speech production models and their digital implementations.

The Digital Signal Processing Handbook [Ebook]. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press.

Retrieved from http://www.dsp-book.narod.ru/DSPMW/44.PDF.

Tatham, M., & Morton, K. (2011). A Guide to Speech Production and Perception [Ebook]. Edinburg: Edinburgh University Press. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/lancaster/detail.action?docID=71413

Leave a comment