In this essay I will be discussing the advantages and disadvantages of being bilingual or monolingual in terms of which languages are spoken, similarities between languages learnt, and effects on cognitive decline.

Lingua Franca (LF)

An obvious advantage to being bilingual is increasing the number of people with whom one can communicate with, which results in an individual increasing “their social circles and granting increased opportunities for employment” (Antoniou, 2018, p.396). As defined by Culpeper, J., Kerswill, P., Wodak, R., McEnery, A., & Katamba, F. (2018, p.348), a lingua franca is used “as a common language between speakers or writers for all of whom it is a second or foreign language.” Therefore, it is most advantageous, communicatively speaking, for bilinguals and monolinguals alike to be able to speak a language commonly used as LF.

As stated by Culpeper et al. (2018), English is a common lingua franca used increasingly in place of national languages in formal circumstances. As said by Phillipson (2010, p.87), “English is increasingly the dominant language both in EU affairs and in many societal domains in continental Europe.” This is further supported by Culpeper et al. (2018), who state that English is used commonly in continental Europe in higher education. Phillipson (2010) argues that continental universities seeking to increase foreign students often require courses to be taught through English and the national language. Consequently, it is advantageous for both monolinguals and bilinguals to be able to speak English when considering studying at higher education or working within a professional sector in Europe.

As stated by Culpeper et al. (2018, p.349), “English has a special role in the youth”, being heavily incorporated into their everyday media use. As supported by Phillipson (2010, p.84), “70-80% of all TV fiction shown on European TV is American” and in an example provided by Culpeper et al. (2018, p.349), “adolescents may use English among themselves while playing computer games”. This daily media incorporation in addition to English’s significant role in education results in a generational advantage to bilingualism, with younger generations being the most benefitted from it. Once again, monolinguals of English are also advantaged but mostly so in countries where the national language is English.

Phoneme Discrimination in Infants

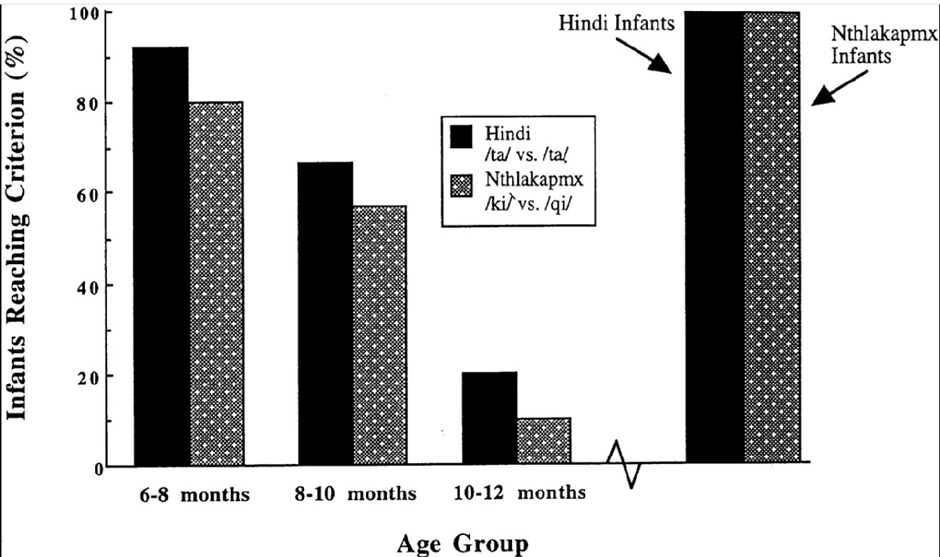

Another generational difference in the advantages of bilingualism is found in infants. Research has found that the phonetic units of many different languages can be discriminated between by infants who are resultantly called universal listeners, this ability includes languages infants are yet to be exposed to (Kuhl, Williams, Lacerda, Stevens & Lindblom, 1992; Werker & Tees, 1999). As found by Kuhl et al. (1992), exposure from a specific language alters this ability significantly by 6 months of age. Werker & Tees (1999) found that phonetic discrimination diminished significantly by 10 months – as shown in Figure 1 below – which was from a previous study of theirs in 1984. Moreover, Kuhl et al. (1992) state that the ability to perceive phonetic differences is reduced in adults when phonemes in other languages act as allophones in an individual’s native language. Therefore, for the ability to perceive speech sound differences in another language, it is most advantageous for bilinguals to be exposed to this language before adulthood, and even better before 10 months.

It is also clearly implied that individuals will find it easier to learn and distinguish between another language’s speech sounds when there is greater frequency of phonetic overlap with their own. As a result, bilinguals may find it easier to learn languages than monolinguals as their perception of speech sounds will be broader.

Despite this, it has been found that speaking in a second language does not require consistently accurate phoneme usage for communicative meaning to be understood. As argued by Culpeper et al. (2018), non-standard features of English such as /ð/ being substituted with /d/ for example did not lead to breakdowns in communication when English was used as a LF. Therefore, although most phonemes do need to be accurately used, the advantage bilinguals have over monolinguals when learning a new language is dependent on how phonetically similar an individual’s first language is to the one they are learning.

Dyslexia

It is not just phonetic similarity between languages which determines how advantageous bilingualism is but orthographic similarity. Research has found that orthographic complexity increases diagnosis of dyslexia (Ziegler & Goswami, 2005; Wydell & Butterworth, 1999; Brunswick, McDougall & de Mornay Davies, 2010), which is a “common learning difficulty that can cause problems with reading, writing and spelling” (“Dyslexia”, 2018). As stated by Ziegler & Goswami (2005), it is not the incidences of dyslexia across orthographies that differs but its manifestation.

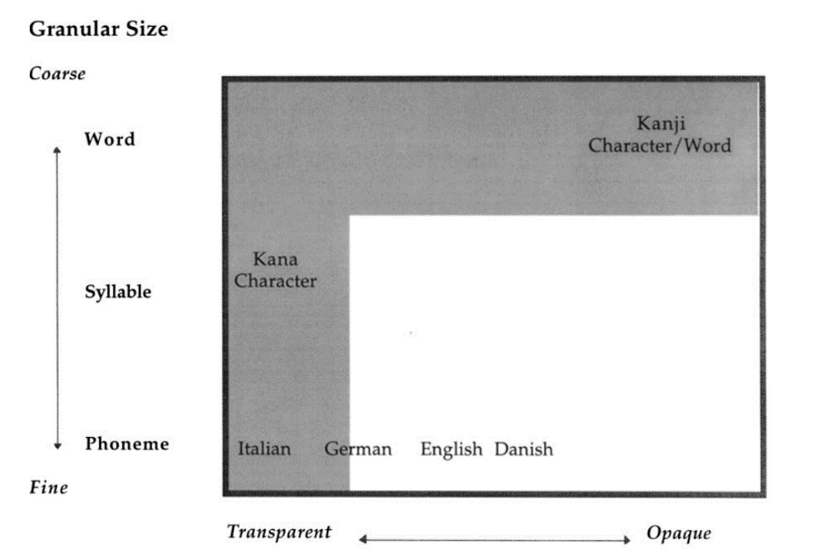

The ‘Hypothesis of Granularity and transparency’, proposed by Wydell & Butterworth (1999), suggests that phonetic and logographic alphabets have lower instances of diagnosed dyslexia. As shown in Figure 2 below, Wydell & Butterworth (1999) categorized languages on a spectrum of transparency (degree of phoneme-to-grapheme correspondence) and granularity (how words are read in terms of unit size).

Under this hypothesis, Brunswick et al. (2010) summarize that slow but accurate reading characterizes dyslexic readers of more transparent orthographies, whilst inaccurate and slow reading characterizes dyslexic readers of opaque orthographies. Therefore, for dyslexic bilingual readers it would be most advantageous to have one or both of their languages being of the transparent form , and as shown in Figure 2, either of the very fine or very coarse variety.

From this research, it could be argued that dyslexic monolingual individuals who speak a language with a transparent orthography would benefit from remaining monolingual as to reduce the risk of discovering they have dyslexia. As explained by Alexander-passe (2015), dyslexia often indirectly impacts negative effects on mental health – such as depression and anxiety; in this context, a dyslexic monolingual may have better mental health by remaining monolingual. However, this view ignores the benefits of diagnosis and advantages to being bilingual which could equally have a positive impact upon mental health.

Moreover, there are great advantages to dyslexic individuals being bilingual not only for mental health but for educational success. In terms of mental health, dyslexic readers could benefit from learning another language in which their symptoms will be less severe, which could, resultantly, have positive implications upon mental health.

In educational terms, dyslexic readers would advance better in a language with a more transparent orthography. As stated by Brunswick et al. (2010), in the United Kingdom some schools now offer Japanese in the curriculum as it has been considered an ideal language to be learnt by dyslexic readers; this has been successful, with proficiency of second language study exceeding previous levels in dyslexic readers. Therefore, bilingualism in this context would be advantageous allowing dyslexic individuals to perform equally to their non-dyslexic peers.

Recall of Words

It is not just dyslexia that impacts bilinguals’ success in language, but the impact bilingualism has on recall. As explained by Paradowski (2011), studies have found bilinguals lag behind their monolingual peers in terms of recall of vocabulary. In both speed and quantity bilinguals scored lower than monolinguals when naming words from categories, demonstrating that recall of words for monolinguals was easier than for bilinguals in each of their spoken languages; this could resultantly mean a higher speech fluency (Paradowski, 2011).

This is further supported by Portocarrero, Burright & Donovick (2007), who found that semantic fluency in bilinguals was significantly lower than monolinguals. Despite this, Portocarrero et al. (2007) argues that the bilinguals would likely have had a larger vocabulary than the monolinguals when considering both languages, as well as that “having a smaller English vocabulary does not necessarily outweigh the benefits of knowing another language and being familiar with another culture” (Portocarrero, et al., 2007, p.420).

Therefore, bilinguals are disadvantaged in this way and monolinguals advantaged, but neither by any means significantly. As proposed by Gollan & Acenas (2004) and summarised by Paradowski (2011, p.346), “[bilinguals] have been found to more frequently experience the ‘tip-of-the-tongue’ phenomenon, i.e. forget the word they wanted to use in conversation”. Although this is a disadvantage of multilingualism, it is not significant, and can be said to be far outweighed by the advantages of speaking another language.

Alzheimer’s Disease

Recall has also been shown to be positively impacted through bilingualism in terms of cognitive aging. There is evidence suggesting that bilingualism could have a positive effect on neuropathological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease. Antoniou (2019) reviewed several studies which all supported the later diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in bilingual individuals as compared to monolinguals. Antoniou (2019) found that these studies all supported a delayed diagnosis of Alzheimer’s in bilinguals, such as Chertkow et al. (2010) and Woumans et al. (2015) where both reported a 4–5-year delay in diagnosis. Moreover, a six-year delay was found in those with low-education (Antoniou, 2019). Therefore, in the context of preventative strategies for this disease, bilingualism holds further benefit than monolingualism especially for illiterate or poorly educated individuals.

However, these results have been challenged by Livingston et al. (2017) who argued that a metanalysis revealed that prospective studies have shown no protection offered by bilingualism from dementia or cognitive decline. This is significant as it infers that retrospective studies found bilingualism to be causally linked to later diagnosis when in fact there was no such correlation. Antoniou (2019) concluded from these contradicting studies that differences in criteria constituting to the definitions of bilingualism and monolingualism affected their results, therefore the effects of bilingualism in this context is still debated. However, although it cannot be concluded that bilingualism is as an advantage in this context, it most certainly is not disadvantageous.

Conclusion

From the discussion above, I have concluded that bilingualism is more advantageous than monolingualism in most circumstances. However, determining how advantageous are factors considering which languages a bilingual speaks, how related phonetically and orthographically these languages are to one another, and the age of the bilingual individual.

References

Alexander-Passe, N. (2015). Dyslexia and Mental Health: Helping people identify destructive behaviours and find positive ways to cope. Jessica Kingsley. Retrieved from https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=4W4NCgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA9&dq=alexander&ots=FbeAP4ODUR&sig=ToWnofsrXY51mJ7TU2WbPfNbrfY&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=alexander&f=false

Antoniou, M. (2019). The advantages of bilingualism debate. Annual Review of Linguistics, 5, 395-415. Annual Reviews. The Advantages of Bilingualism Debate. Retrieved from https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-linguistics-011718-011820?casa_token=HrKaxXg1yPQAAAAA:6aQzhVEhqsvvH-SCfWQC2BiL_MRSFzDpRx-Z5OtQ7tJP1p2IAREIRVx3tQq2r8vVkZk4eUoq3w

Brunswick, N., McDougall, S., & de Mornay Davies, P. (Eds.). (2010). Reading and dyslexia in different orthographies. ProQuest Ebook Central. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

Culpeper, J., Kerswill, P., Wodak, R., McEnery, A., & Katamba, F. (Eds.). (2018). English language : Description, variation and context. ProQuest Ebook Central. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com.

Dyslexia. (2018). Retrieved 26 April 2021, from https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/dyslexia/

Kuhl, P. K., Williams, K. A., Lacerda, F., Stevens, K. N., & Lindblom, B. (1992). Linguistic experience alters phonetic perception in infants by 6 months of age. Science, 255(5044), 606-608. Retrieved from https://science.sciencemag.org/content/255/5044/606.abstract?casa_token=qRVWkaxKgdsAAAAA:0JRqSSH00Q6ccOxjZH-JObZ4eNxHsW3x5ltlWNosVcscfKdyAQtrXDQEweCdFcjKEnSGl36fW8E

Livingston, G., Sommerlad, A., Orgeta, V., Costafreda, S. G., Huntley, J., Ames, D., … & Mukadam, N. (2017). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. The Lancet, 390(10113), 2673-2734. Retrieved from https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(17)31363-6/fulltext?elsca1=etoc

Paradowski, M. B. (2011). Multilingualism–assessing benefits. Issues in Promoting Multilingualism Teaching–Learning–Assessment, 335-354. Retrieved from http://czytelnia.frse.org.pl/media/issues-promoting-multilingualism-1.pdf#page=336

Phillipson, R. (2010). Linguistic Imperialism Continued. (1st ed.). Florence: Routledge. ProQuest Ebook Central. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

Portocarrero, J. S., Burright, R. G., & Donovick, P. J. (2007). Vocabulary and verbal fluency of bilingual and monolingual college students. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 22(3), 415-422. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/acn/article/22/3/415/2985?login=true

Werker, J. F., & Tees, R. C. (1999). Influences on infant speech processing: Toward a new synthesis. Annual review of psychology, 50(1), 509-535. Retrieved from https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.509?casa_token=OtdAqFple80AAAAA:Q2qrVCjKP9fVIkNNVtxzsV_a74HBJmEx9xeHBU63svs3OfrA762T234MqH-RF2OLB09seROW6g

Wydell, T. N., & Butterworth, B. (1999). A case study of an English-Japanese bilingual with monolingual dyslexia. Cognition, 70(3), 273-305. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0010027799000165?casa_token=Fewj3o9oVuMAAAAA:U1iFJobkbxWjymEzR8eR0qiwuvQ3LQj39jGHGO2DxzGXWevnINhFbrWOwRJ1-g5tGPlMCfk

Ziegler, Johannes C, & Goswami, Usha. (2005). Reading Acquisition, Developmental DysDiscuss whether is it an advantage or a disadvantage to be a bilingual, and under what particular circumstances.

In this essay I will be discussing the advantages and disadvantages of being bilingual or monolingual in terms of which languages are spoken, similarities between languages learnt, and effects on cognitive decline.

Lingua Franca (LF)

An obvious advantage to being bilingual is increasing the number of people with whom one can communicate with, which results in an individual increasing “their social circles and granting increased opportunities for employment” (Antoniou, 2018, p.396). As defined by Culpeper, J., Kerswill, P., Wodak, R., McEnery, A., & Katamba, F. (2018, p.348), a lingua franca is used “as a common language between speakers or writers for all of whom it is a second or foreign language.” Therefore, it is most advantageous, communicatively speaking, for bilinguals and monolinguals alike to be able to speak a language commonly used as LF.

As stated by Culpeper et al. (2018), English is a common lingua franca used increasingly in place of national languages in formal circumstances. As said by Phillipson (2010, p.87), “English is increasingly the dominant language both in EU affairs and in many societal domains in continental Europe.” This is further supported by Culpeper et al. (2018), who state that English is used commonly in continental Europe in higher education. Phillipson (2010) argues that continental universities seeking to increase foreign students often require courses to be taught through English and the national language. Consequently, it is advantageous for both monolinguals and bilinguals to be able to speak English when considering studying at higher education or working within a professional sector in Europe.

As stated by Culpeper et al. (2018, p.349), “English has a special role in the youth”, being heavily incorporated into their everyday media use. As supported by Phillipson (2010, p.84), “70-80% of all TV fiction shown on European TV is American” and in an example provided by Culpeper et al. (2018, p.349), “adolescents may use English among themselves while playing computer games”. This daily media incorporation in addition to English’s significant role in education results in a generational advantage to bilingualism, with younger generations being the most benefitted from it. Once again, monolinguals of English are also advantaged but mostly so in countries where the national language is English.

Phoneme Discrimination in Infants

Another generational difference in the advantages of bilingualism is found in infants. Research has found that the phonetic units of many different languages can be discriminated between by infants who are resultantly called universal listeners, this ability includes languages infants are yet to be exposed to (Kuhl, Williams, Lacerda, Stevens & Lindblom, 1992; Werker & Tees, 1999). As found by Kuhl et al. (1992), exposure from a specific language alters this ability significantly by 6 months of age. Werker & Tees (1999) found that phonetic discrimination diminished significantly by 10 months – as shown in Figure 1 below – which was from a previous study of theirs in 1984. Moreover, Kuhl et al. (1992) state that the ability to perceive phonetic differences is reduced in adults when phonemes in other languages act as allophones in an individual’s native language. Therefore, for the ability to perceive speech sound differences in another language, it is most advantageous for bilinguals to be exposed to this language before adulthood, and even better before 10 months.

It is also clearly implied that individuals will find it easier to learn and distinguish between another language’s speech sounds when there is greater frequency of phonetic overlap with their own. As a result, bilinguals may find it easier to learn languages than monolinguals as their perception of speech sounds will be broader.

Despite this, it has been found that speaking in a second language does not require consistently accurate phoneme usage for communicative meaning to be understood. As argued by Culpeper et al. (2018), non-standard features of English such as /ð/ being substituted with /d/ for example did not lead to breakdowns in communication when English was used as a LF. Therefore, although most phonemes do need to be accurately used, the advantage bilinguals have over monolinguals when learning a new language is dependent on how phonetically similar an individual’s first language is to the one they are learning.

Dyslexia

It is not just phonetic similarity between languages which determines how advantageous bilingualism is but orthographic similarity. Research has found that orthographic complexity increases diagnosis of dyslexia (Ziegler & Goswami, 2005; Wydell & Butterworth, 1999; Brunswick, McDougall & de Mornay Davies, 2010), which is a “common learning difficulty that can cause problems with reading, writing and spelling” (“Dyslexia”, 2018). As stated by Ziegler & Goswami (2005), it is not the incidences of dyslexia across orthographies that differs but its manifestation. The ‘Hypothesis of Granularity and transparency’, proposed by Wydell & Butterworth (1999), suggests that phonetic and logographic alphabets have lower instances of diagnosed dyslexia. As shown in Figure 2 below, Wydell & Butterworth (1999) categorized languages on a spectrum of transparency (degree of phoneme-to-grapheme correspondence) and granularity (how words are read in terms of unit size). Under this hypothesis, Brunswick et al. (2010) summarize that slow but accurate reading characterizes dyslexic readers of more transparent orthographies, whilst inaccurate and slow reading characterizes dyslexic readers of opaque orthographies. Therefore, for dyslexic bilingual readers it would be most advantageous to have one or both of their languages being of the transparent form

, and as shown in Figure 2, either of the very fine or very coarse variety.

From this research, it could be argued that dyslexic monolingual individuals who speak a language with a transparent orthography would benefit from remaining monolingual as to reduce the risk of discovering they have dyslexia. As explained by Alexander-passe (2015), dyslexia often indirectly impacts negative effects on mental health – such as depression and anxiety; in this context, a dyslexic monolingual may have better mental health by remaining monolingual. However, this view ignores the benefits of diagnosis and advantages to being bilingual which could equally have a positive impact upon mental health.

Moreover, there are great advantages to dyslexic individuals being bilingual not only for mental health but for educational success. In terms of mental health, dyslexic readers could benefit from learning another language in which their symptoms will be less severe, which could, resultantly, have positive implications upon mental health.

In educational terms, dyslexic readers would advance better in a language with a more transparent orthography. As stated by Brunswick et al. (2010), in the United Kingdom some schools now offer Japanese in the curriculum as it has been considered an ideal language to be learnt by dyslexic readers; this has been successful, with proficiency of second language study exceeding previous levels in dyslexic readers. Therefore, bilingualism in this context would be advantageous allowing dyslexic individuals to perform equally to their non-dyslexic peers.

Recall of Words

It is not just dyslexia that impacts bilinguals’ success in language, but the impact bilingualism has on recall. As explained by Paradowski (2011), studies have found bilinguals lag behind their monolingual peers in terms of recall of vocabulary. In both speed and quantity bilinguals scored lower than monolinguals when naming words from categories, demonstrating that recall of words for monolinguals was easier than for bilinguals in each of their spoken languages; this could resultantly mean a higher speech fluency (Paradowski, 2011). This is further supported by Portocarrero, Burright & Donovick (2007), who found that semantic fluency in bilinguals was significantly lower than monolinguals. Despite this, Portocarrero et al. (2007) argues that the bilinguals would likely have had a larger vocabulary than the monolinguals when considering both languages, as well as that “having a smaller English vocabulary does not necessarily outweigh the benefits of knowing another language and being familiar with another culture” (Portocarrero, et al., 2007, p.420). Therefore, bilinguals are disadvantaged in this way and monolinguals advantaged, but neither by any means significantly. As proposed by Gollan & Acenas (2004) and summarised by Paradowski (2011, p.346), “[bilinguals] have been found to more frequently experience the ‘tip-of-the-tongue’ phenomenon, i.e. forget the word they wanted to use in conversation”. Although this is a disadvantage of multilingualism, it is not significant, and can be said to be far outweighed by the advantages of speaking another language.

Alzheimer’s Disease

Recall has also been shown to be positively impacted through bilingualism in terms of cognitive aging. There is evidence suggesting that bilingualism could have a positive effect on neuropathological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease. Antoniou (2019) reviewed several studies which all supported the later diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in bilingual individuals as compared to monolinguals. Antoniou (2019) found that these studies all supported a delayed diagnosis of Alzheimer’s in bilinguals, such as Chertkow et al. (2010) and Woumans et al. (2015) where both reported a 4–5-year delay in diagnosis. Moreover, a six-year delay was found in those with low-education (Antoniou, 2019). Therefore, in the context of preventative strategies for this disease, bilingualism holds further benefit than monolingualism especially for illiterate or poorly educated individuals.

However, these results have been challenged by Livingston et al. (2017) who argued that a metanalysis revealed that prospective studies have shown no protection offered by bilingualism from dementia or cognitive decline. This is significant as it infers that retrospective studies found bilingualism to be causally linked to later diagnosis when in fact there was no such correlation. Antoniou (2019) concluded from these contradicting studies that differences in criteria constituting to the definitions of bilingualism and monolingualism affected their results, therefore the effects of bilingualism in this context is still debated. However, although it cannot be concluded that bilingualism is as an advantage in this context, it most certainly is not disadvantageous.

Conclusion

From the discussion above, I have concluded that bilingualism is more advantageous than monolingualism in most circumstances. However, determining how advantageous are factors considering which languages a bilingual speaks, how related phonetically and orthographically these languages are to one another, and the age of the bilingual individual.

References

Alexander-Passe, N. (2015). Dyslexia and Mental Health: Helping people identify destructive behaviours and find positive ways to cope. Jessica Kingsley. Retrieved from https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=4W4NCgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA9&dq=alexander&ots=FbeAP4ODUR&sig=ToWnofsrXY51mJ7TU2WbPfNbrfY&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=alexander&f=false

Antoniou, M. (2019). The advantages of bilingualism debate. Annual Review of Linguistics, 5, 395-415. Annual Reviews. The Advantages of Bilingualism Debate. Retrieved from https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-linguistics-011718-011820?casa_token=HrKaxXg1yPQAAAAA:6aQzhVEhqsvvH-SCfWQC2BiL_MRSFzDpRx-Z5OtQ7tJP1p2IAREIRVx3tQq2r8vVkZk4eUoq3w

Brunswick, N., McDougall, S., & de Mornay Davies, P. (Eds.). (2010). Reading and dyslexia in different orthographies. ProQuest Ebook Central. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

Culpeper, J., Kerswill, P., Wodak, R., McEnery, A., & Katamba, F. (Eds.). (2018). English language : Description, variation and context. ProQuest Ebook Central. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com.

Dyslexia. (2018). Retrieved 26 April 2021, from https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/dyslexia/

Kuhl, P. K., Williams, K. A., Lacerda, F., Stevens, K. N., & Lindblom, B. (1992). Linguistic experience alters phonetic perception in infants by 6 months of age. Science, 255(5044), 606-608. Retrieved from https://science.sciencemag.org/content/255/5044/606.abstract?casa_token=qRVWkaxKgdsAAAAA:0JRqSSH00Q6ccOxjZH-JObZ4eNxHsW3x5ltlWNosVcscfKdyAQtrXDQEweCdFcjKEnSGl36fW8E

Livingston, G., Sommerlad, A., Orgeta, V., Costafreda, S. G., Huntley, J., Ames, D., … & Mukadam, N. (2017). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. The Lancet, 390(10113), 2673-2734. Retrieved from https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(17)31363-6/fulltext?elsca1=etoc

Paradowski, M. B. (2011). Multilingualism–assessing benefits. Issues in Promoting Multilingualism Teaching–Learning–Assessment, 335-354. Retrieved from http://czytelnia.frse.org.pl/media/issues-promoting-multilingualism-1.pdf#page=336

Phillipson, R. (2010). Linguistic Imperialism Continued. (1st ed.). Florence: Routledge. ProQuest Ebook Central. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

Portocarrero, J. S., Burright, R. G., & Donovick, P. J. (2007). Vocabulary and verbal fluency of bilingual and monolingual college students. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 22(3), 415-422. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/acn/article/22/3/415/2985?login=true

Werker, J. F., & Tees, R. C. (1999). Influences on infant speech processing: Toward a new synthesis. Annual review of psychology, 50(1), 509-535. Retrieved from https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.509?casa_token=OtdAqFple80AAAAA:Q2qrVCjKP9fVIkNNVtxzsV_a74HBJmEx9xeHBU63svs3OfrA762T234MqH-RF2OLB09seROW6g

Wydell, T. N., & Butterworth, B. (1999). A case study of an English-Japanese bilingual with monolingual dyslexia. Cognition, 70(3), 273-305. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0010027799000165?casa_token=Fewj3o9oVuMAAAAA:U1iFJobkbxWjymEzR8eR0qiwuvQ3LQj39jGHGO2DxzGXWevnINhFbrWOwRJ1-g5tGPlMCfk

Ziegler, Johannes C, & Goswami, Usha. (2005). Reading Acquisition, Developmental Dyslexia, and Skilled Reading Across Languages. Psychological Bulletin, 131(1), 3-29. Retrieved from http://web.b.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.lancs.ac.uk/ehost/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=1980703a-0438-46c9-aa1b-93b5377e177a%40sessionmgr103&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3dlexia, and Skilled Reading Across Languages. Psychological Bulletin, 131(1), 3-29. Retrieved from http://web.b.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.lancs.ac.uk/ehost/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=1980703a-0438-46c9-aa1b-93b5377e177a%40sessionmgr103&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d

Leave a comment