Table of Content

- Literature Review

- Background : Trophy Hunting in Bwabwata National Park

2.1. Population & Colonial Histories

2.2. Unequal Benefit Distribution - Research Aims

3.1. Objectives - Methods

4.1. Research Design & Ethics

4.1.1. Community-based Participatory Research (CBPR)

4.1.2. Mixed Methods Research (MMR)

4.1.3. Ethics Procedure

4.2. Study Site

4.3. Sampling & Techniques

4.3.1. Qualitative

4.3.1.1. Sampling for SSIs

4.3.1.2. Stratified Sampling for Community FGs

4.3.1.3. Convenience Sampling for Livelihood PO

4.3.2. Quantitative

4.3.2.1. Surveys

4.3.2.2. WSPD

4.4. Analysis Plan

4.4.1. Lead Researchers (LRs) & Research Assistants (RAs)

4.4.2. NVivo

4.4.3. Open Data Kit

4.4.4. RStudio - Logistics and Schedule

5.1. Language Barriers

5.2. Validity of Data

5.3. Compensation

5.4. Schedule - References

- Appendices: Draft Version of Tools

List of Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Description |

| BNP | Bwabwata National Park |

| CBNRM | Community Based Natural Resource Management |

| CBO | Community Based Organisations |

| CBPR | Community Based Participatory Research |

| FG (o/y/ml/mm/mh/fl/fm/fh/FG) | Focus Group: (older/younger; male/female; low/middle/high socio-economic group e.g. oflFG) |

| IRDNC | Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation (a BNP NGO) |

| KA | Kyaramacan Association: a CBNRM CBO representing BNP residents |

| KAMs | Kyaramacan Association Members |

| lrs | Lead Researchers |

| MET | Ministry of Environment and Tourism |

| MMR | Mixed Methods Research Design |

| NGO | Non Governmental Organisation |

| NSC | Namibian San Council |

| PO | Participant Observation |

| PR | Park Rangers |

| QGIS | Quantum Geographic Information System (Software) |

| RA | Research Assistants |

| SEG | Socio-Economic Group |

| TH | Trophy Hunting |

| VLs | Village Leaders |

| VMs | Village Members |

| WIMSA | Working Group of Indigenous Minorities in Southern Africa |

| WSPD | Wildlife Species Population Data |

Glossary

- * – Fabricated Data

- omiramba – seasonally flooded drainage lines

- Veldfood – Bush Food (fruits, etc.)

Acknowledgements

This project has received all required permissions in addition to expressions of support from the MET, NSC, KA, and IRDNC*.

Cover Photograph curtesy of ‘Nature Travel Africa’ (2021).

1. Literature Review

This is a two-year participatory ethnographic research proposal to evaluate the impacts of Trophy Hunting (TH), a Community Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) programme, in Bwabwata National Park (BNP) in Namibia. The project will evaluate the CBNRM’s impacts in terms of wildlife conservation, household economies and livelihoods, and community development. Community development will be defined by the building of new infrastructure (e.g. roads, schools, etc.), gender benefits, and community attitudes towards the scheme.

CBNRM is a land management and conservation strategy which assumes that enabling rural communities to manage and benefit from their land, often through tourism ventures, will promote sustainable practices and meet government conservation and development goals (MET, 2013). Community Based Organisations (CBOs), formed of community members, are given legislative authority over land areas to create and enforce sustainable management practices. These are supported by the private, civil and government sectors whilst the overall decision making is done by the local community. For long-term sustainability of CBNRMs, it is imperative that revenue must continue to both fund conservancy operational costs and benefit community members either personally or through local community development. Therefore, continued government funding, expansion of income streams, and revenue growth (often through external investors) are essential.

TH is a sport in which large game are hunted for a fee often through a private company as a tourism venture under government licence (Thomsen et al., 2021). TH is a conservation strategy employed in sub-Saharan Africa to preserve wildlife species. TH CBNRMs can provide revenue for community conservation initiatives and employment (Koot, 2019). However, local empowerment and participation are essential for the sustainability of TH practices as otherwise unsustainable practices will resume. Unfortunately, CBNRM schemes are known for exacerbating unequal benefit distributions between gender and socio-economic groups (SEGs).

2. Background: TH in the Bwabwata National Park (BNP)

TH is just one CBNRM that occurs in the BNP in Namibia. The BNP, located in the Caprivi strip and Kavango regions, covers 6,100km2 land (Jones & Dieckmann, 2014). The BNP is a part of the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA) which includes areas within Botswana, Angola, and Zambia (Paksi & Pyhälä, nd.). The BNP’s geographical characteristics include nutrient-poor Kalahari sands, riparian vegetation, the Okavango and Kwando Rivers, and their omiramba and flood plains. As typical of sub-Saharan Africa, the BNP holds large game species like lions and elephants.

CBNRM Activities started in 1992 which included ecotourism, souvenir making, game guarding by community members and sustainable harvesting, but the first TH initiatives started in 2006 (Koot, 2019). Kyaramacan Association (KA) is a CBNRM association formed in 2004 that represents everyone living in the park. It receives investment from TH companies, licensed by the Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET), which bring in money from tourism, employing locals (tracking and skinning) and funding. TH concessions across 2006-2007 brought in N$1.2 million and 36 tons of game meat distributed to the people in the BNP. The KA are also responsible for funding community projects such as higher education and community gardens (Jones & Dieckmann, 2014).

2.1. Population & Colonial Histories

Approximately 5000 people of different ethnic groups live within the BNP’s 17 villages including the majority Khwe san (80%) and the minority groups !Xun san (16%) and Mumbukshu (4%), amongst others (Jones & Dieckmann, 2014) Inter-ethnic tensions persist, specifically, the increasing settlement of Mumbukshu post-1920s has increased conflict with the Khwe San (Jones & Dieckmann, 2014).

Pre-colonial rule, the San community was an egalitarian society with no one political figure, open decision-making discussions and open access to resources (Sylvain, 2010). Traditionally, the San were hunter-gatherers and had extensive knowledge of indigenous flora and fauna. The arrival of the white labouring system resulted in gendered roles with women becoming domestic servants with lower wages. San men were treated as household breadwinners and thus were paid more. Consequently, a patriarchal system began to evolve.

From 1884-1915, Namibia was colonised by Germany and “mandated to South Africa as a Trust Territory in 1920” (Sylvain, 2011). Under apartheid rule, 40% of agricultural land was given to white settlers, local people experienced land loss, forced labour and marginalisation. Since the 1990s, postcolonial CBNRMs have been employed in Namibia which enabled communities to benefit from and manage game animals which overruled the previous Nature Conservation Ordinance of 1975. However, the current CBNRM restricts certain livelihood practices, although inhabitants can cultivate the land for agriculture, keeping cattle beyond a marker and hunting is prohibited.

Post independence, Khwe and !Xun San have been prioritised under the Agricultural Land Reform Act of 1995 to be resettled but this has benefited only a few San people. Many San are attempting to move out of government reservations to establish settlements (World directory of minorities and Indigenous Peoples, 2008). However, a report by the United Nations Development Programme has shown that the San have had the lowest life expectancies, are at higher risk of the Aid epidemic and been affected most by the country’s increasing poverty.

2.2. Unequal Benefit Distribution

TH also makes organisations and communities dependent on them for income (Paksi & Pyhälä). The KA is heavily reliant on income from TH and communities like the San (who used to hunt for food) now depend on the government and NGOs (Thomsen et al., 2021). This is changing community-wildlife relationships which several community members expressed concern over. Additionally, research has shown that the majority of TH revenue goes to private companies and only 3% goes to the community (Koot, 2019). The MET receives 50% of hunting revenue which is distributed across Namibia rather than solely within the BNP (Jones & Dieckmann, 2014 ). Additionally, employment within the BNP is limited due to its national park status (Jones & Dieckmann, 2014) with TH only employing 12 locals and the KA only employing 36 (Paksi & Pyhälä, nd). Moreover, bribery allegations have been made against the KA, NGOs and TH operators which has fostered an atmosphere of mistrust around TH (Koot, 2019).

Additionally, despite colonialism disempowering women and making men the household breadwinners, independence has resulted in the opposite benefits. Women’s income shares have increased and gendered labour activities such as crafts and gathering are still permitted under CBNRM rules. However, men’s activities like hunting became prohibited and contractual employment on farms was reduced making many women core providers (Koot, 2019).

3. Research Aims

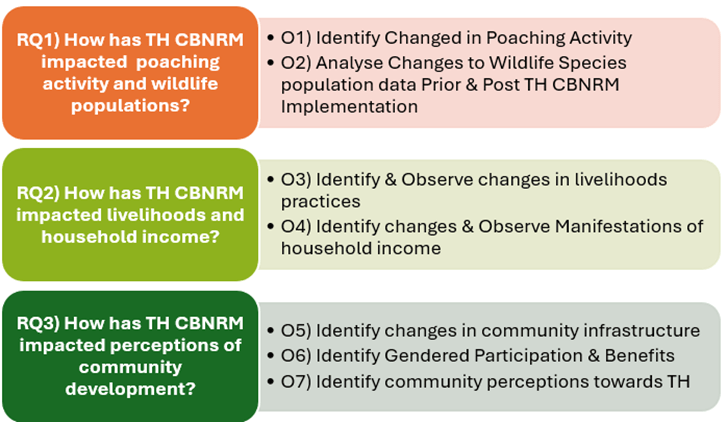

The study aims to answer the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1) How has TH CBNRM impacted poaching activity and wildlife populations?

RQ2) How has TH CBNRM impacted livelihoods and household income?

RQ3) How has TH CBNRM impacted perceptions of community development in terms of gender benefits, SEGs, and attitudes?

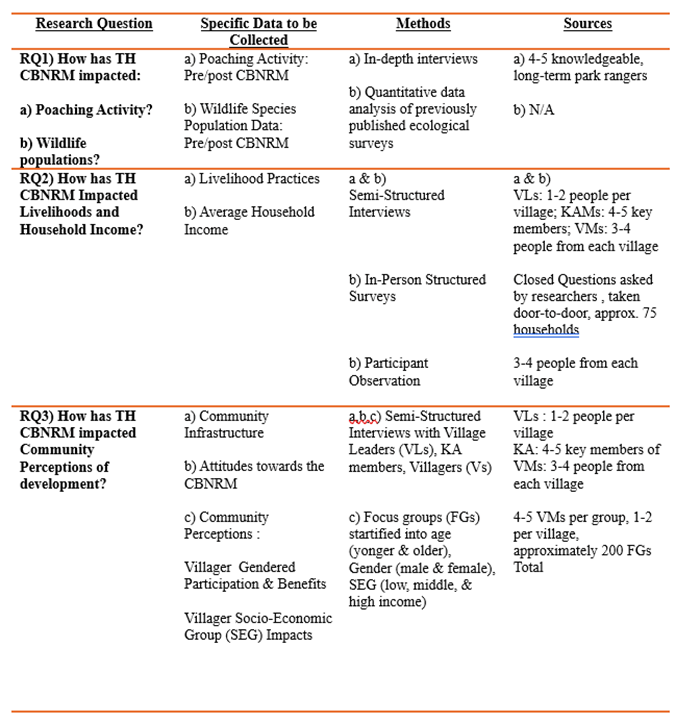

All objectives aim to uncover how TH CBNRM has resulted in change from pre/post CBNRM implementation (see Figure 1) and correspond to a particular method (see Figure 2). Our hypotheses below outline TH CBNRM’s expected outcomes in relation to the RQs.

- H1) Decreased rates of illegal wildlife harvesting and increased numbers of wildlife species populations

- H2) Demonstration of both positive and negative community perceptions, with issues raised around the loss of cultural ecosystem services, loss of access to traditional subsistence means, and uneven distribution of benefits

- H3) Diversification of livelihoods to include TH as a significant contributor, accomapnised by an income increase, but evidence of income inequality being exacerbated

- H4) Heightened gender inequality as men have opportunities for work but also face conflict where traditional harvest and trophy hunting clashes

4. Methods

4.1. Research Design & Ethics

4.1.1. Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR)

We will use a CBPR design with MMR approaches to gain a thorough understanding of TH impacts in the BNP. CBPR is the involvement of community members to identify problem research areas and seek solutions whilst empowering local communities, valuing community knowledge, and balancing research power relations (Leavy, 2017). CBPR can be used for evaluative research to define culturally specific terminologies (e.g. development) and integrate community perspectives into research tools. Producing a decolonised framework which can help build rapport and avoid offence is important considering the BNP’s colonial histories and current tensions with TH companies. Figure 2 outlines our proposed CBPR model.

To achieve CBPR, we will co-produce SSIs, FG Sessions, Surveys, and define key terminologies with CBOs (KA), VLs, NGOs (IRDNC etc.), and Village Members (VMs) (Jones & Dieckmann, 2014; Leavy 2017). CBPR designs require longer time periods due to their method modifications from community feedback (Leavy, 2017) which is possible with our two-year timeframe. This flexible research design means that the provided methods and tools (see Appendices) are subject to change.

4.1.2. MMR

We will use an MMR approach which is useful for evaluating complex scenarios such as TH CBNRMs (Leavey, 2017). Qualitative data will include semi-structured interviews (SSIs), villager Focus Groups (FGs), and Participant Observation (PO), whilst quantitative data will include household surveys and comparison of MET provided WSPD*. Our quantitative and qualitative data sets will be complementary and produce a more insightful understanding to the data (Leavy, 2017). Qualitative data will be collected first to inform later research; specifically, interviews with Key Figures will be used to inform FGs and quantitative surveys. Sampling could change due to variables in the field. MMR can better provide information on individual experience, context and prevalence (Leavy, 2017)

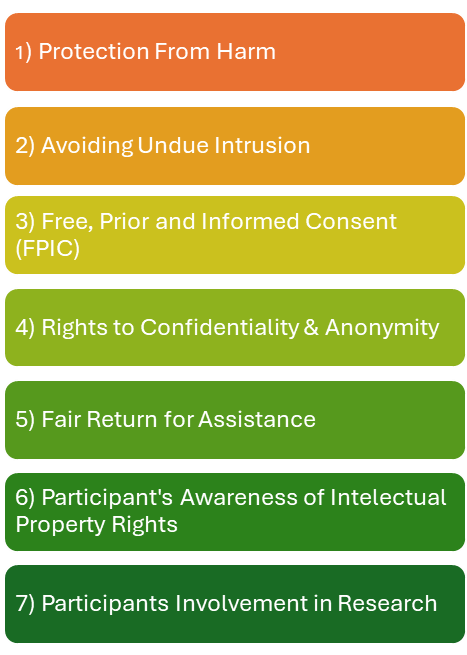

4.1.3. Ethics Procedure

Ethical praxis will meet the requirements for IRB approval, the Namibian San Council (NSC), and follow the Figure 3 model. NSC approval occurs when the ‘The San Code of Research Ethics’, including central values (Care, Respect, Honesty, Fairness) and community approval process, are met (Schroeder, D. et al., 2019). No harm should come to participants during research and CBPR design will mitigate anticipated harm through responsive methodologies. CBPR will also prevent undue intrusion through mitigation of intrusive questions; participants will also be informed of their right to withdraw data at any time. All Participants will receive full research disclosure and provide regularly renewed FPIC. All participant data will be anonymised (Household IDs & pseudo-anonymisation) and stored on encrypted devices. CBPR design and providing community gifts ensures that participants receive involvement and fair return for assistance.

4.2. Study Site

Namibia was chosen as a site for TH CBNRM evaluation due its extensive colonial history which has impacted current BNP communities (see Background). Secondly, Namibia has no hunting ban history unlike other sub-Saharan countries like Uganda & Kenya (Lindsy, 2008) which would act as a confounding variable to the evaluation of WSPD. The BNP also has numerous ongoing community projects with NGOs with strong relationships to communities in which to partner with. These factors will help with our project’s success, enabling us to build rapport faster and gain community-based participation.

4.3. Sampling & Techniques

4.3.1. Qualitative

4.3.1.1. Sampling for SSIs. We will use purposive sampling for SSIs with Key Figures: Park Rangers (PRs), Village Leaders (VLs), and KA Members (KAMs). Purpose sampling is suited to CBPR designs as it ensures interviews with specific, community relevant individuals (Leavy, 2017). We will interview 3-5 knowledgeable PAs, 1-2 VLs per village, and 4-5 KAMs. Sample sizes are based upon expectations of participant availability and the limited numbers of people representing these community organisations. Simple random sampling will be used for VM SSIs and the sample determined by using baseline BNP population data provided by the MET (2020*) and an online random number generator. 3-5 VMs per village will be used with a total sample size of approximately 85 participants.

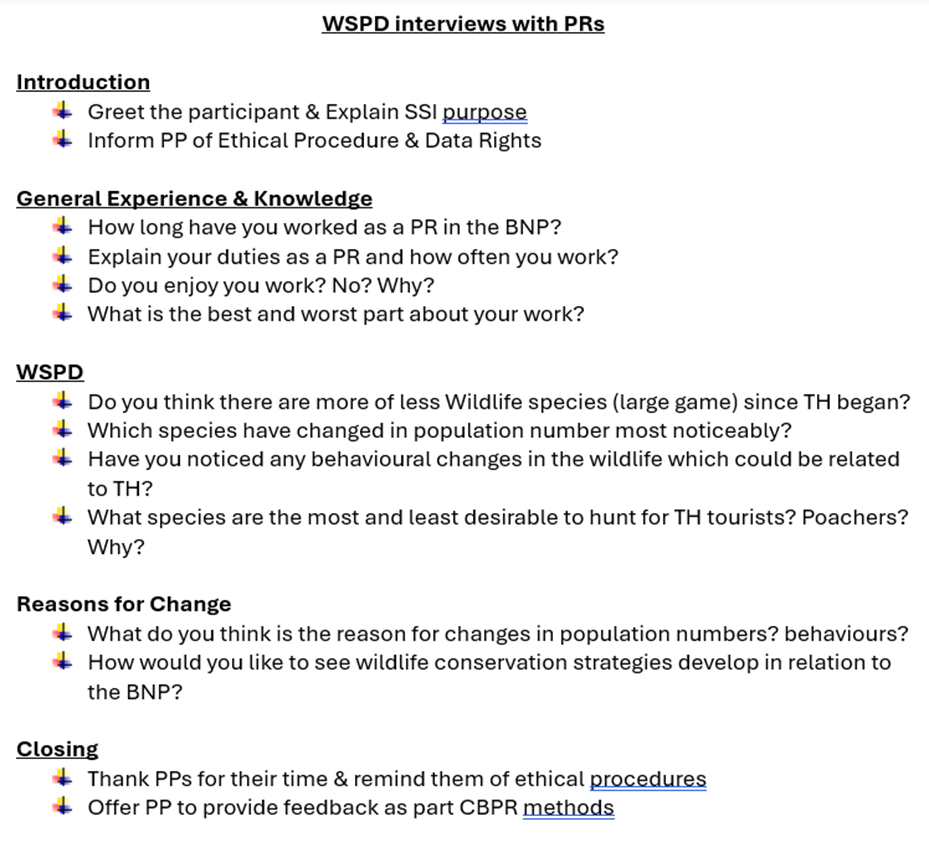

SSIs. We will be conducting in-person SSIs with PRs, VLs, KAMs, and VMs which will be conducted in private locations (e.g. participant houses). SSIs will enable us to build on prior knowledge whilst enabling Participants to expand on relevant topics (Bernard, 2011) which contributes to a community-led framework. LRs and RAs will use interview guides to ensure topics of interest are covered in order.

PR interviews will investigate changes in illegal hunting rates, approximate WSPD and the wildlife targeted since TH CBNRM implementation. Participating PRs will have worked in the park since before CBNRM started or who are knowledgeable about WSPD trends to increase interrater reliability. These interviews will enable researchers to gain a more thorough understanding of changes in illegal hunting without putting participants at increased risk.

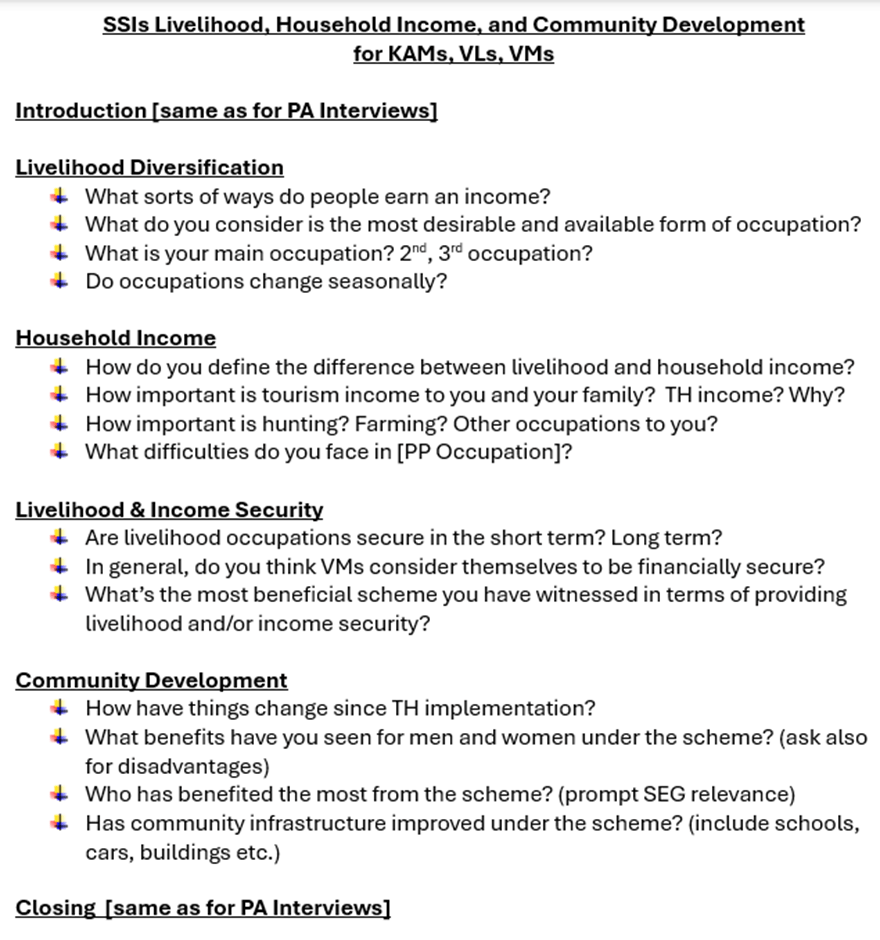

Interviews with VLs, KAMs, and VMs will provide insight into community perceptions of development in relation to village infrastructure, livelihoods and household income (occupation diversification, income sources and stability), impacts on gender and SEGs, and general attitudes towards the scheme. However, VLs and KAMs interviews will occur first to aid the co-production of interview guides for VMs, providing information unavailable within the literature review and enabling a more decolonised approach of concepts.

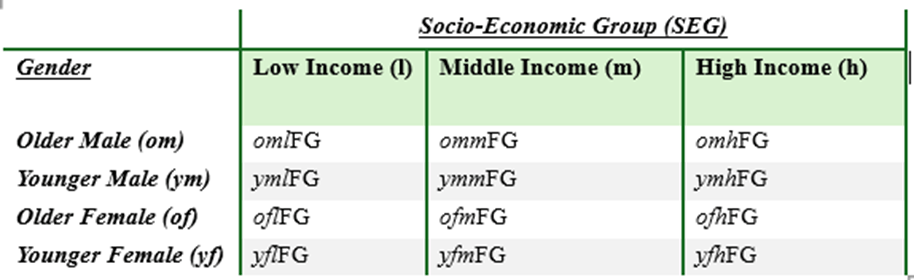

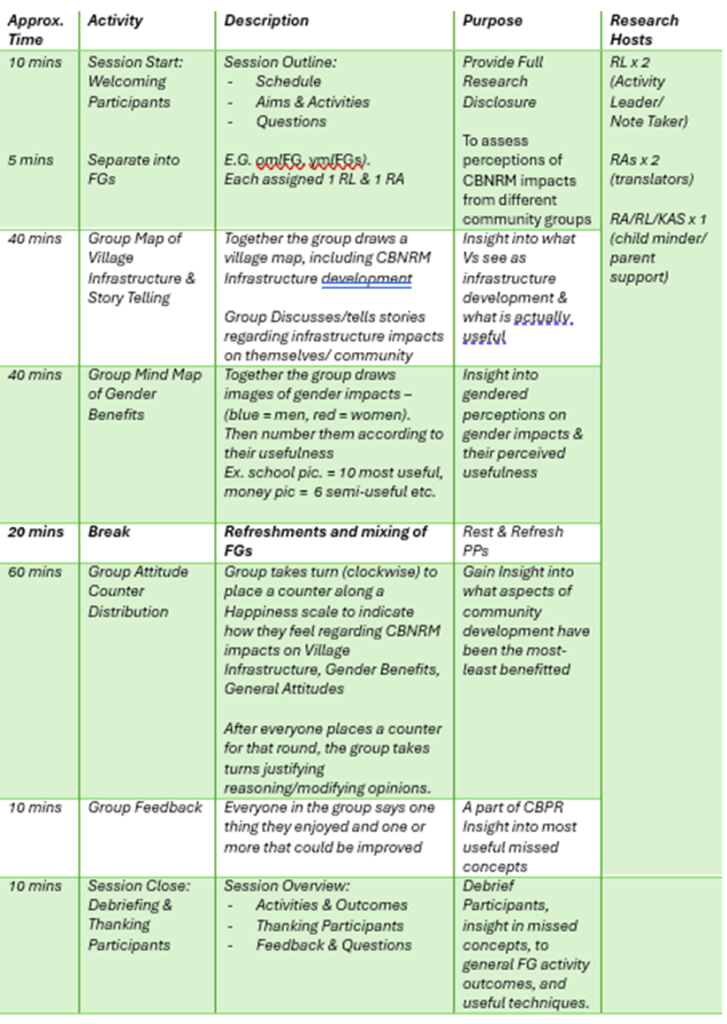

4.3.1.2. Stratified Random Sampling for Community FGs. To evaluate how TH CBNRM has impacted different groups of people we will use stratified random sampling (Bernard, 2011). FGs will be stratified into age, gender and SEGs resulting in twelve different FGs see (Table 2) with 4-5 individuals per FG and 1-2 of each per village. Each FG session will involve one SEG, one gender, and both age FGs, resulting in approximately 360 FGs split across 180 FG sessions in two-years. We chose these strata research due to the large, expected differences of TH CBNRM (Bernard, 2011) as indicated in the ‘Background’. FGs will investigate changes to and community perceptions of, village infrastructure and services, gender and SEG Impacts, and attitudes towards the scheme.

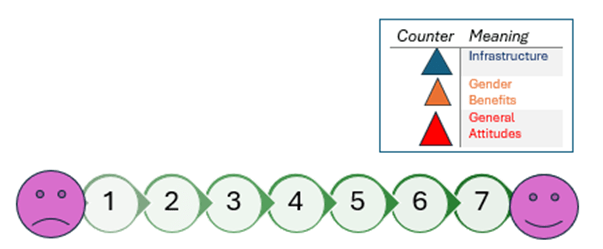

The FG Session guide (see Appendices) outlines a session of FG activities and purposes. No set times have been given as these are subject to changes. Per session, one SEG and both age FGs will be present but separate from one another. There will be two LRs to lead each FG and take notes, two RAs to translate, and another host to provide child-parent support. Session activities will not include writing or reading due to low literacy rates (Jones & Dieckmann, 2014), but will use discussions, drawing, etc. Activities include drawing village infrastructure maps with accompanied storying telling; drawing mind maps of the different gender impacts for men and women and numbering them in order of usefulness; distributing counters representing impacts (either infrastructure, gender, or attitude) on an attitude scale towards CBNRM.

4.3.1.3. Convenience Sampling for Livelihood PO Convenience sampling will be used for PO of livelihood diversification, income sources, and gathering information on gendered labour roles. Convenience sampling is ideal when there is no guarantee of participant engagement (Bernard, 2011); in our case, busy VMs may not want researchers intruding during their working hours, thus we will use a small sample size of 4 VMs per village. These will be conducted twice in each village to account for seasonal change from the dry to the wet season (When to go to NAMIBIA, 2023).

4.3.2. Quantitative

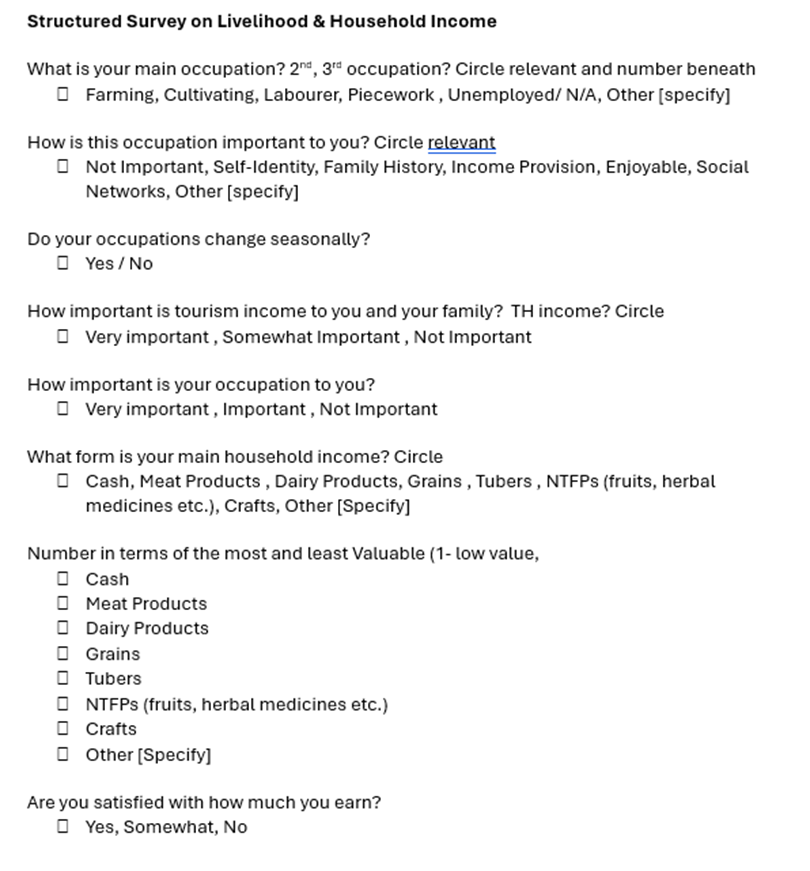

4.3.2.1. Surveys. Surveys will be conducted after qualitative data collection to provide LRs time to become fully informed regarding VMs perceptions of important topics and definitions (e.g. SEGs). Surveys will be co-produced with VLs and KAMs (after Key Figure interviews) to ensure questions are culturally sensitive. These surveys will gather quantitative data on livelihood diversification, dependency, and income stability. Surveys will be conducted in all villages using simple random sampling, after assigning each household with an ID and using a random allocation generator to assign approximately 357 households. This sampling method is appropriate as we want every VM to have an equal chance of being chosen and to use this data to generalise to the whole population (Leavy, 2017). Sample size was determined to be statistically reliable by an online sample size generator recommended by Bernard (2011) at a 95% confidence interval and a 5% Margin of Error for the BNP population of 5000 people.

4.3.2.2. WSPD. Baseline WSPD, collected by the MET* prior to and after TH establishment (MET, 1990; MET, 2020*) will be used to understand if there is a significant difference between wildlife populations. Data sets includes number of different species, species populations, and rates of illegal hunting (including successful and attempted hunts). This WSPD will complement PR interviews by gaining an understanding of how participant bias influences perceptions; it also increases WSPD accuracy due to the large quantitative data set (Leavy, 2017).

4.4. Analysis Plan

4.4.1. Lead Researchers (LRs) & Research Assistants (RAs)

With our funding we will hire six RAs who will be equally assigned to the three LRs. RAs will translate in-person interviews, FG discussions, in-person surveys, and support household inventory collection. RAs will be Namibian citizens hired from within the BNP, recommended by our partner organisations, and will be fluent in English and BNP languages e.g. Khwe (Jones & Dieckmann, 2014). This further involves community members as per our research design and increases data interrater reliability. RAs will include equal numbers of men and women to enable interaction with participants of both genders without infringing on VM’s gender standards.

RAs will be experienced in handling data but will receive training from LRs (see Gantt Chart) to conduct research independently. Training will ensure the understanding of research aims, data program teaching, and interview technique. Additionally, they will provide insight into BNP life, pointing out missed questions and opportunities. LRs and RAs will meet after each data collection day to debrief each other on data collection progress.

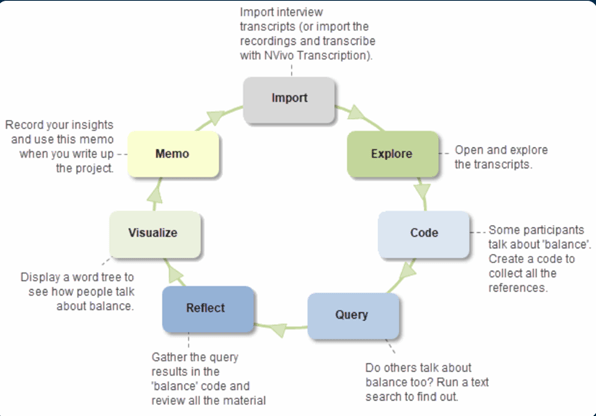

4.4.2. NVivo

SSIs, FG discussions, and PO data will be transcribed and analysed using automatic thematic coding on NVivo (lumivero, 2023). We will use the iterative analysis model (Figure 5) to continuously update our understanding of qualitative data as more is added.

4.4.3. Open Data Kit & RStudio

We will use Open Data Kit (ODK) to design research tools (surveys, interviews), securely store and export data, reduce entry time, and work offline where appropriate (ODK, nd.). Not all villages will have access to internet and thus a reliable secure data storage tool with automatic syncing is desirable. Moreover, it will enable LRs and RAs to collect data paper free which will be especially useful for the surveys which can instead be filled in by the RAs on their phones.

RStudio will be used to conduct statistical analysis on quantitative data. We will use a paired t-test to determine if there is a significant difference between the means of the two MET provided WSPD* (Leavy, 2017). Surveys will be analysed using basic descriptive statistics (standard deviation etc.) which will be used to analyse distribution of different livelihoods and household incomes.

5. Logistics & Schedule

5.1. Language Barriers

VMs in the BNP only speak local languages such as Khwe and !Xun; additionally, literacy rates amongst residents is very low due to a lack of financial resources (Jones & Dieckmann, 2014). Thus, it is necessary to employ local RAs who are multilingual in English and BNP languages to act as translators for all research activities. Additionally, all activities must use writing and reading alternatives such as drawing and storytelling.

5.2. Validity of Data

Confounding variables threaten the validity of infrastructure and community development perceptions data. Multiple organisations support community development projects beyond TH and could cause data misinterpretation when assessing TH outcomes. The Ministry of Lands and Resettlement supports development projects (e.g. sanitation services), the MET licences TH concessions and funds anti-poaching patrols, and the government provides food aide. Several NGOs also fund community projects including the IRDNC, WIMSA, and the Women’s leadership Centre (Jones & Dieckmann, 2014). However, data misinterpretation can be mitigated through the CBPR Collaborative Data Analysis phase and community feedback.

5.3. Compensation

Another issue was regarding how to provide incentives and compensation for participation in our research project. Monetary compensation can cause rivalry between community members and leave compensation expectations for future researchers. Therefore, we propose providing community gifts such as communal cooking pots or returning later to support a development project. Additionally, the CBPR approach means that community members are benefitted by engaging with research as they can share their ideas on community matters.

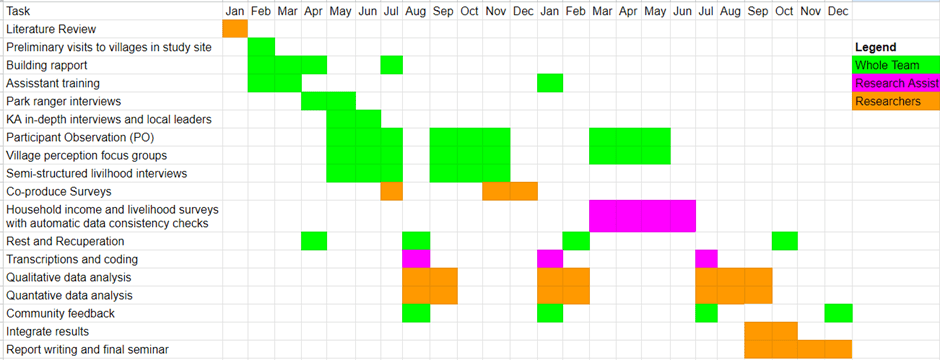

5.4. Schedule

The Gantt chart shows research activity delegation over the two-year timeframe. Four months of rapport building facilitates building researcher-community relationships with VMs and partner organisations, enables LRs to conduct preliminary CBPR collaboration, and researchers to settle into their BNP village accommodation. This will ensure participants understand and feel the research involves them and is relevant to their experiences.

RA training overlaps with report building ensuring the whole research team builds rapports with VMs before research begins. Qualitative research occurs first to enable informed and co-produced quantitative tools. There are also several, month-long, rest periods throughout the project to prevent researcher burn-out and return to their home countries. Data analysis also overlaps with these rest periods as a less strenuous activity. Additionally, community feedback is gathered after every block of qualitative data collection, with a final collection occurring upon report completion to return to the village.

6. References

About Us (2015) kyaramacan.wordpress.com. Available at: https://kyaramacan.wordpress.com/about/ (Accessed: 20 March 2024).

‘Association of Social Anthropologists of the UK and the Commonwealth (ASA) ’ (2019) ASA Ethical Guidelines 2011 [Preprint]. Available at: https://theasa.org/downloads/ASA%20ethics%20guidelines%202011.pdf (Accessed: 2024).

Bernard, H.R. (2011) Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. 5th edn, VLeBooks. 5th edn. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. Available at: https://r2.vlereader.com/Reader?ean=9780759112438 (Accessed: 2024).

Bruce, C.D., Flynn, T. and Stagg-Peterson, S. (2011) ‘Examining what we mean bycollaborationin Collaborative Action Research: A cross-case analysis’, Educational Action Research, 19(4), pp. 433–452. doi:10.1080/09650792.2011.625667.

Collect data anywhere (no date) ODK. Available at: https://getodk.org/ (Accessed: 21 March 2024).

Jones, B. & Dieckmann, Ute. (2014). Chapter 10: Bwabwata National Park. In Diekmann, J., Thiem, M., Dirkx, E., Hays, J. “Scraping the Pot”: San in Namibia Two Decades After Independence (pp. 365-298). Natural Justice. Retrieved from: https://www.lac.org.na/projects/lead/Pdf/scraping_two_chap10.pdf

Koot, S. (2019) ‘The limits of economic benefits: Adding social affordances to the analysis of trophy hunting of the Khwe and ju/’hoansi in Namibian community-based natural resource management’, Society & Natural Resources , 32(4), pp. 417–433. doi:10.1080/08941920.2018.1550227.

Leavy, P.L. (2017) Research design: Quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, arts-based, and community-based participatory research approaches, ProQuest Ebook CentralTM. New York: The Guilford Press. Available at: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ucl/reader.action?docID=4832778# (Accessed: 2024).

Lindsey, P.A., 2008. Trophy hunting in sub-Saharan Africa: economic scale and conservation significance. Best practices in sustainable hunting, 1, pp.41-47.

Namibia. Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET) Directorate of Parks & Wildlife Management (2013). National Policy on Community Natural Resource Management. Available at: https://www.npc.gov.na/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/National-Policy-on-Community-Based-Natural-Resources-Management-March-2013.pdf (Accessed at March 2024).

(2021) Nature Travel Africa. Bwabwata National Park. Available at: https://naturetravelafrica.com/bwabwata-national-park/ (Accessed: 2024).

Paksi , A. and Pyhälä, A. (no date) ‘Socio-economic Impacts of a National Park on Local Indigenous Livelihoods: The Case of the Bwabwata National Park in Namibia’, in R.F. Puckett and K. Ikeya (eds.) Research and Activism among the Kalahari San Today: Ideals, Challenges, and Debates. SENRI ETHNOLOGICAL STUDIES, pp. 197–214. Available at: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Socio-economic+Impacts+of+a+National+Park+on+Local++Indigenous+Livelihoods%3A+The+Case+of+the+Bwabwata+National+Park+in+Namibia&btnG= (Accessed: 2024).

Sample size calculator (2023) Qualtrics. Available at: https://www.qualtrics.com/blog/calculating-sample-size/ (Accessed: 21 March 2024).

Schroeder, D. et al. (2019) ‘The San Code of Research Ethics ’, in Equitable Research Partnerships: A Global Code of Conduct to Counter Ethics Dumping. Springer Link, pp. 73–87. Available at: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-15745-6 (Accessed: 2024).

Sylvain, R. (2011) ‘At the intersections: San women and the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Africa’, The International Journal of Human Rights, 15(1), pp. 89–110. doi:10.1080/13642987.2011.529690.

Thomsen, J.M. et al. (2021) ‘Community perspectives of empowerment from trophy hunting tourism in Namibia’s Bwabwata National Park’, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(1), pp. 223–239. doi:10.1080/09669582.2021.1874394.

Vivo product tour – discover the power of NVivo (2023) Lumivero. Available at: https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo/nvivo-product-tour/ (Accessed: 19 March 2024).

When to go to Namibia (month by month): Wayfairer Travel (2023) WAYFAIRER. Available at: https://www.wayfairertravel.com/destinations/namibia/when-to-go-to-namibia/ (Accessed: 2024).

World directory of minorities and Indigenous Peoples – Namibia : SAN (2008) Refworld. Available at: https://www.refworld.org/reference/countryrep/mrgi/2008/en/64944 (Accessed: March 2024).

7. Appendices: Draft Version of Tools

Below are some example drafts of the research tools we will be using. Not all have been provided but all are subject to change.

Example : FG Session

Session

Examples of Interview Guides for SSIs :

Figure 12: Livelihood, Household Income, & community development SSI Interview Guide for KAMs, VLs, and VMs

Example of Livelihood and Income Survey

Leave a comment