This essay outlines how land use change impacts the Kayapo indigenous group living in Southern Brazil. I will begin by introducing the Kayapo and how their lifestyle depends on their environment, then I will explain the impacts of changes in land cover uses (gold mining, deforestation, and hydroelectric dams) on the Kayapo, before concluding with the expected future implications for their communities.

The Kayapo (or the Mebengokre) are an indigenous group living in the Para and Mato Grosso states of Brazil (Zimmerman et al., 2001). Population data varies but estimates suggest approximately 9000 people live across three legally ratified and two non-ratified indigenous reserves (Zimmerman et al., 2001; Schwartzman et al., 2013). These reserves encompass 13 million ha of land which are made up of forest and cerrado (savanna) (Zimmerman et al., 2001). Their livelihoods rely on subsistence production including from fishing, swidden agriculture, foraging and hunting (Turner, 2013).

The Kayapo are experts of their environment, viewing it as a series of ecozones with various subdivisions (Posey, 2002, pp. 58-81). Ecozones have specific flora, fauna, and soil types which affect hunting strategies and choice of land use. The Kayapo gather medicines, material resources, and food from the forest. Men form hunting parties, whilst women gather, garden, and complete domestic work (Beckham, 1989).

The Kayapo employ shifting agriculture and, using a mixture of organic mulch and crushed termites, plant useful species in savanna regions (Posey, 2002, pp. 55-57). Fallow fields grow into managed secondary forest which make hunting grounds and grow useful plants. Indigenous knowledge and resource management provide much needed alternatives to global homogenous models (Posey, 2002, p. 224).

However, land use changes such as deforestation, mining, and hydroelectric dam construction increasingly threaten their land, worsen climate change impacts, and threaten the existence of Kayapo living (Schwartzman et al., 2013).

Land Cover Uses

Gold mining

Since the 1970s, Brazil has been experiencing a gold rush, which was initially supported by the Brazilian government to distract from social conflicts like the Landless Worker’s Movement (Turner, 1995). This mining has caused deforestation, mercury pollution, flooding, and related increases in malaria cases. In addition, mining regions have experienced a rise in violent conflicts and human infectious diseases. The indigenous missionary council states that all these impacts are harmful to indigenous groups (WWF, 2006b; Turner, 1995). Gold mining threatens the Kayapo as their territory’s eastern border holds the Serra Pelada and Cumaru goldmines which later led to illegal mines operating on Kayapo land (Turner, 1995; Turner, 2013).

Mercury

In addition to the impacts of clearing land for mining (see ‘Deforestation’), local communities are exposed to mining-related mercury pollution caused by using mercury to extract gold from alluvium by forming an amalgam (Palheta & Taylor, 1995; Turner, 1995). Metallic mercury is released into the aquatic environment, and the air by heating this amalgam. Common practice of riverbed dredging using Bolsa boats carries a higher chance of mercury contamination than traditional mining, this occurs in Mato Grosso’s Teles Pires River (WWF, 2006b). Water contamination results in fish, and animals in contact with the water, also becoming contaminated. As mercury accumulates up the food chain, predators gain higher mercury dosages (Palheta & Taylor, 1995).

Studies have found that Kayapo communities have high levels of mercury contamination. Pregnant women in Gorotire and Kikretum (Kayapo villages with nearby mines) have had pregnancy issues and birth defects (Turner, 1995; Turner, 2013). Mercury poisoning includes both physical symptoms (e.g. organ damage.) and neurological (e.g. memory loss) (UK Health and Security Agency, 2022). Palheta and Taylor (1995) measured mercury pollution in human inhabitants, animal tissues, and water which demonstrated widespread mercury contamination in the Amazon region.

However, despite organisations educating indigenous and non-indigenous communities on mercury’s dangers, illegal mining and Kayapo-granted concessions remain prevalent (Turner, 1995).

Malaria

Placer mining techniques also result in flooding land areas which become breeding grounds for malaria-carrying mosquitos (Turner, 1995). South American miners are susceptible to mosquito bites as they work long hours outside, often living in open-air camps with poor hygiene and limited health care (Recht et al., 2017). As Malaria parasites can be carried by humans into new areas, increasing contact with miners has led to malaria cases increasing in the Kayapo and other indigenous groups (Wetzler et al., 2022). Indigenous communities have limited healthcare access and their isolated environments have led to less malaria data collection which limits preventative aid (Recht et al., 2017). Further Kayapo deaths are expected with increasing external contact as vaccines have not been manufactured for all diseases threatening indigenous communities because of widespread urban population immunity (Salzano & Hurtado, 2004).

Political Activism & Concessions

Mining is also affecting Kayapo lives through the increasing need to become politically active and negotiate concessions with illegal miners to protect their environment. In the 1980s, two illegal mines, within walking distance of the Gorotire Kayapo village, were taken over by 200 armed Kayapo (Turner, 2013). This was significant for the government negotiating a Kayapo reserve in return for a two-year extension on the mines closure and providing the Kayapo with a profit (Turner, 1995). This income was used to purchase a plane in which to monitor Kayapo territory and dispatch patrols to threatened areas; this method was successful in massively reducing extractive activities on Kayapo land (Turner, 2013).

However, after this period, the Kayapo continued to run the mines, open new ones, and grant concessions to illegal miners; Kayapo leaders used these concessions to supply their communities with basic services like healthcare which the government stopped in the 1990s (Turner, 1995). Despite this, some Kayapo leaders used this money to fund elite lifestyles which led to a loss of environmentalist and NGO support who had advocated for Kayapo control over their resources (Turner, 1995). This demonstrates that the Kayapo are adapting to mining threats by utilising political negotiations, modern technologies, and illegal methods (conflict and monetary agreements) to protect their lifestyles.

Deforestation

Deforestation has many damaging effects such as biodiversity and soil nutrient loss, erosion and flooding, water pollution, and CO2 increase (Posey, 2002, p. 58). Deforestation caused by land cover activities and climate change also increases the risk of forest fire (Fonseca et al., 2019). Gottlieb (1981:23 as cited in Posey, 2002) predicts that 90 per cent of organisms living in the Amazon basin will go extinct before their documentation due to deforestation. These effects threaten Kayapo livelihoods by depleting natural resources and biodiversity on which they depend.

Logging

The ‘arc of deforestation’ refers to the most south-eastern curve of the Amazon rainforest in which deforestation is most rapid (NASA Earth Observatory, 2004). Kayapo territory is protected with its reservation status whilst surrounding deforestation has almost tripled between 2000-2018 (Conservation International, 2014; Langlois, 2022; Zimmerman et al., 2001). However, illegal logging does occur on Kayapo land and high market prices encourage loggers (Zimmerman et al., 2001). Illegal mahogany logging occurs in all of Para state’s indigenous reserves and incentives for reforesting or logging sustainably, are minimal with short-term concessions (Verissimo et al., 1995; WWF, 2006a). Logging decreases game and, therefore, decreases food sources for indigenous people which is increasing malnutrition among indigenous communities, causing health and fertility issues (Watson, 1996). A moratorium on Brazilian mahogany logging was suggested by Watson (1996).

Despite this, the Kayapo argue that they need concessions with illegal loggers to earn an income when the government fails to fund services, despite understanding deforestation’s impacts (Watson, 1996). Concessions have created a positive relationship between parties, demonstrated when illegal loggers funded some Kayapo to protest the outlawing of logging on Kayapo reserves (Turner, 2013; Watson, 1996). However, Indigenous communities are often cheated out of a fair economic gain due to little market experience (Watson, 1996). The Xikirin of Catete, a Kayapo subgroup, entered a concession in which they profited 60 times less than the selling price (WWF, 2006a; CEDI, 1993 as cited in Watson, 1996). Therefore, the Kayapo find themselves becoming reliant on concessions and cheated out of a fair profit.

Soy

Deforestation for industrialised soy farming also results in decreasing biodiversity (Lopes et al., 2021). Indigenous groups with demarcated territory, like the Kayapo, still risk their livelihoods and food sovereignty due to industrialised soy farming. Moreover, climate change, and the clearing of cerrado vegetation, have caused a shorter planting season and increased cases of drought; this has put pressure on farmers to invest in powerful hydraulic pumps which take unregulated quantities from rivers and groundwater. Lack of water quota monitoring concerning monoculture has put increasing pressure on the water basin which local people have become concerned with. Pesticides used for soy farming also cause water pollution resulting in health problems, pregnancy issues, and infant deaths. These pesticides also result in local plants dying which affects local people reliant on them (Lopes et al., 2021). As the Kayapo are dependent on rivers and land, all these effects are extremely concerning to their livelihoods.

Access: Roads and Railways

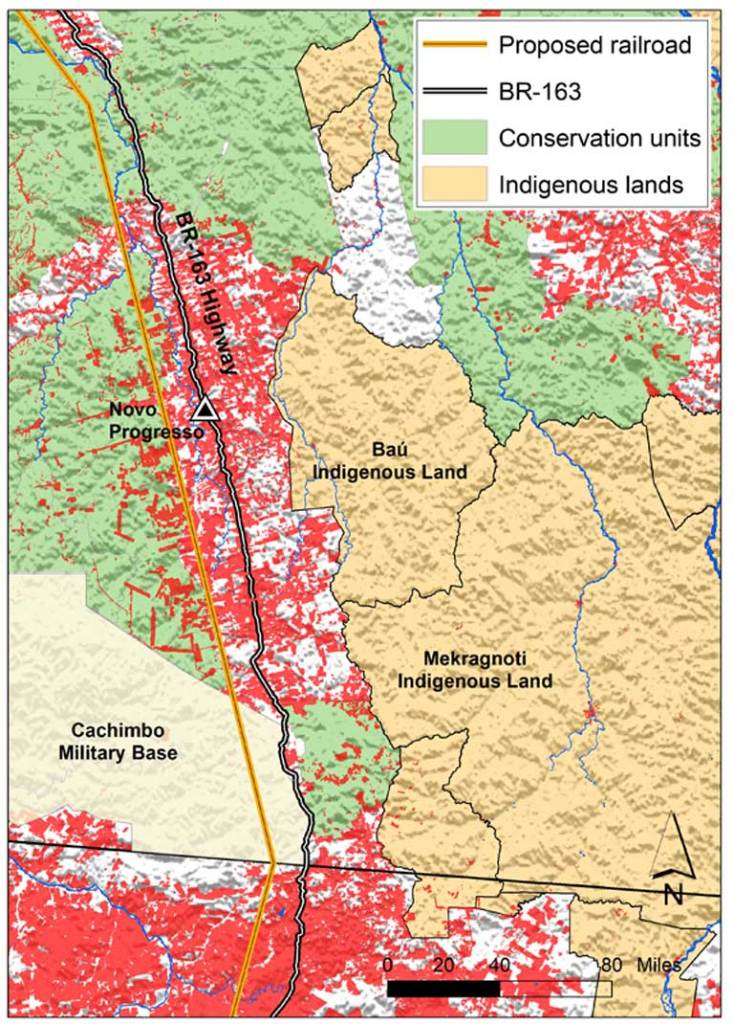

Increasing access to isolated areas in the Para and Mato Grosso states threatens Kayapo living. The BR-163 road runs parallel to Kayapo land and has increased deforestation which impacts the environment’s biodiversity on which the Kayapo depend (Conservation International, 2012; Posey, 2002, p. 58). This road was built predominantly to facilitate regional soy export and thus is contributing to the impacts of soy agriculture (see ‘Soy’) (Langlois, 2022). Moreover, 3000 km of roads have been built to facilitate logging transportation in Southern Para which has increased Kayapo land access and the spread of outsider diseases (Verissimo et al., 1995; Watson, 1996). This is concerning for the Kayapo, as the BR-163 motorway’s paving led to the near elimination of the Panara indigenous group from conflict and disease (WWF, 2006b). Additionally, as deforestation tends to spread outwards from new roads, it is expected that more roads equal more land clearance (NASA Earth Observatory, 2004). Concerningly, a railway may be built near Kayapo land to facilitate soybean export; this will facilitate access to and expansion of soybean agriculture (Langlois, 2022).

(Mongabay, 2020, https://imgs.mongabay.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2020/08/25105432/REV-map-768-Kayapo%CC%81.jpg)

Hydroelectric Dams

Greater electricity demands and the pursuit of sustainable electricity sources have led to Brazil’s construction increase of hydroelectric dams which are deemed cheaper and more sustainable than alternatives (IJHD, 2010, & Prado et al., 2016 as cited in Lees et al., 2016). Furthermore, the aim to process rather than just export domestic resources is another contributing factor to increased interest in hydroelectric power (Lees et al., 2016). Therefore, hydroelectric power will likely increase interest in extractive activities which will impact Kayapo lifestyles (see ‘Mining’ and ‘Deforestation’).

Dams impact a river’s organismal migration, sediment and nutrient transportation, water depth, flow rates, water quality deterioration, and changes to seasonal flood pulses (Lees et al., 2016). Fish experience migratory obstruction, loss of seasonal spawning triggers, loss of habitat niches, and a favouring of invading species (Lees et al., 2016). Currently, Hydroelectric dams are threatening 71 species of freshwater Amazonian River basin fish according to Brazil’s Ministry of Environment (2014, as cited in Lees et al., 2016). As the Kayapo rely on fishing as a food source, declines in edible fish would be detrimental to their protein intake and lifestyle.

Belo Monte

In 2010, the Belo Monte dam’s construction was approved, which displaced thousands of indigenous people (initially expected to include Kayapo) and flooded 500 km2 of rainforest (Eptimov, 2022). Diverting the Xingu River, dramatically reduced flow in the Volta Grande, which has deprived aquatic species of breeding grounds and dramatically impacted fishing communities. Despite its promised energy production of 11.000mw per month, the dam has never surpassed 7000mw; moreover, deforestation and climate change are extending the dry season which means the dam’s energy output will decrease with time. Despite Belo Monte’s negative environmental impacts, Kayapo territory did not experience flooding or drying out (Eptimov, 2022). However, the dam’s massive overall effect on the region’s landscape and biodiversity will impact the Kayapo.

Belo Monte’s construction has enabled a gold mining company to access the exposed riverbed which will contribute to harmful environmental impacts (see ‘Mining’) (Poierer, 2012, as cited in Lees et al., 2016). By 2031, Belo Monte is also expected to cause an additional 4000-5000km2 worth of deforestation. Additionally, a third of endemic species living in the Xingu River are now threatened with extinction due to its construction (Lees et al., 2016). Furthermore, transportation is made more economically efficient when dam construction develops waterways which facilitates exports (Castello et al., 2013 as cited in Lees et al., 2016). This is particularly relevant to soybean transportation, whose agriculture is a major contributor to the region’s deforestation which affects the Kayapo (see ‘Deforestation’).

Political Activism

Land cover threats to the Kayapo are impacting their lifestyles by making them more politically active. Before the Belo Monte dam, the Xingu Hydroelectric Dam Project proposed to construct nine dams along the Xingu River (Posey, 2002, pp. 225-233). In 1989, the Kayapo organised a demonstration to protest the Karaoa dam (later Belo Monte); this resulted in mass media attention and the World Bank cancelling the loan (Crocker, 1991). However, the Belo Monte dam’s construction was later approved in 2010 (Hall & Branford, 2012). Moreover, two Kayapo chiefs, who had internationally advocated for indigenous rights and environmental protection, were falsely accused of rape and murder (Eptimov, 2022; Posey, 2002, pp. 232-233). I believe, with their increasing political activism, further cases of defamation will arise against the Kayapo. However, as the uniting of Kayapo tribes and international protests were so successful, I believe the Kayapo will become increasingly engaged in political protests and international media to protect their livelihoods. For example, some tribes have formed alliances with NGOs and indigenous rights groups to gain international support (Zimmerman, 2013).

Conclusion

As explained, land cover change has a significant impact on Kayapo living. The effects on the Kayapo range from impacts on health, environmental degradation and access to livelihood resources, economic changes through concession granting, and social issues ranging from physical conflicts to political activism. This essay demonstrates, that for the Kayapo lifestyle to survive, more governmental support is needed to provide access to services (like healthcare), stricter monitoring of indigenous territory, funding of alternative income schemes, and provision of territory monitoring equipment. Additionally, a supportive political system is essential. Past governments have sought to build economic growth by exploiting indigenous territory through extractive activities, like Jair Bolsanaro’s reign in 2019 (Diele-Vegas et al., 2020).

However, current alliances with NGOs and indigenous rights groups provide the Kayapo with international support (Zimmerman, 2013). NGOs have also financed territory monitory programmes and provided income schemes, like the marketing of Copaiba oil, as an alternative to seeking concessions (Conservation International, 2014). Indigenous lands and protected areas (ILPAs) have dramatically reduced Amazonian rainforest deforestation, including the Kayapo inhabited Xingu region (Schwartzman et al., 2013). With increasing international understanding of climate change, I believe the Kayapo will continue gaining international support which will buffer further inevitable extractive activities on their land which will continue to impact them.

References

Beckham, M. (Director, Producer). (1989). The Kayapo – out of the forest [Film]. Royal Anthropological Institute.

Conservation International. (2012, June 14). Kayapo Fund – English Version. [Video].YouTube. https://youtu.be/L5VZRgYfqJU?si=bdykpj4PuCXRwwqL.

Conservation International. (2014, May). Brazil’s Kayapó – stewards of the Forest. Brazil’s Kayapó – Stewards of the Forest. https://www.conservation.org/projects/brazils-kayapo-stewards-ofthe-forest

Crocker, W. (1991). [Review of the films The Kayapo & The Kayapo: Out of the forest]. American Anthropologist, 92(2), 514-516. https://doi.org/https://www.jstor.org/stable/681374

Diele-Viegas, L. M., Pereira, E. J., & Rocha, C. F. (2020). The new brazilian gold rush: Is amazonia at risk? Forest Policy and Economics, 119, 102270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2020.102270

Evtimov, A. (2022, March 7). The Kayapo stopped the “beautiful monster”, but couldn’t slay it. The Kayapo Project. https://kayapo.org/belo-monte/

Fonseca, M. G., Alves, L. M., Aguiar, A. P., Arai, E., Anderson, L. O., Rosan, T. M., Shimabukuro, Y. E., & de Aragão, L. E. (2019). Effects of climate and land‐use change scenarios on fire probability during the 21st century in the Brazilian Amazon. Global Change Biology, 25(9), 2931–2946. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14709

Langlois, J. (2022, March 29). For the Kayapó, a long battle to save their amazon homeland. Yale E360. https://e360.yale.edu/features/for-the-kayapo-a-long-battle-to-save-their-amazonhomeland

Lees, A. C., Peres, C. A., Fearnside, P. M., Schneider, M., & Zuanon, J. A. (2016). Hydropower and the future of Amazonian Biodiversity. Biodiversity and Conservation, 25(3), 451–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-016-1072-3

Russo Lopes, G., Bastos Lima, M. G., & Reis, T. N. P. (2021). Maldevelopment revisited: Inclusiveness and social impacts of soy expansion over Brazil’s cerrado in Matopiba. World Development, 139, 105316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105316

NASA Earth Observatory. (2004, April). Deforestation patterns in the Amazon. NASA.

%2C%20increasingly%2C%20soybean

Palheta, D., & Taylor, A. (1995). Mercury in environmental and biological samples from a gold mining area in the Amazon region of Brazil. Science of The Total Environment, 168(1), 63–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-9697(95)04533-7

Posey, D. (2002b). Report from Gorotire: will Kayapo traditions survive? In K. Plenderleith (Ed.), Kayapó ethnoecology and culture (pp. 55–57). essay, Routledge.

Posey, D. (2002). Indigenous Knowledge and development: an ideological bridge to the future . In K. Plenderleith (Ed.), Kayapó ethnoecology and culture (pp. 58–81). essay, Routledge.

Posey, D. (2002). The keepers of the forest. In K. Plenderleith (Ed.), Kayapó ethnoecology and culture (pp. 193–199). essay, Routledge.

Posey, D. (2002c). The Kayapo Indian Protests against Amazonian dams: successes, alliances, and unending battles. In K. Plenderleith (Ed.), Kayapó ethnoecology and culture (pp. 223–233). essay, Routledge.

Recht, J., Siqueira, A. M., Monteiro, W. M., Herrera, S. M., Herrera, S., & Lacerda, M. V. (2017). Malaria in Brazil, Colombia, Peru and Venezuela: Current challenges in malaria control and elimination. Malaria Journal, 16(1), 273. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-017-1925-6

Salzano, F. M., & Hurtado, A. M. (Eds.). (2004). Disease Susceptibility among New World People.

In Lost paradises and the ethics of Research and publication. essay, Oxford University Press.

Schwartzman, S., Boas, A. V., Ono, K. Y., Fonseca, M. G., Doblas, J., Zimmerman, B., Junqueira, P., Jerozolimski, A., Salazar, M., Junqueira, R. P., & Torres, M. (2013). The natural and social history of the indigenous lands and Protected Areas Corridor of the Xingu River Basin.

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 368(1619), 20120164. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2012.0164

Turner, T. (1995). An indigenous people’s struggle for socially equitable and ecologically sustainable production: The Kayapo Revolt Against Extractivism. Journal of Latin American

Anthropology, 1(1), 98–121. https://doi.org/10.1525/jlca.1995.1.1.98

Turner, T. (2013). The Kayapo Resistance. In H. Callan, B. Street, & S. Underdown (Eds.), Introductory readings in anthropology (pp. 257–266). essay, Berghahn Books in association with the Royal Anthropological Institute.

UK Health and Security Agency. (2022, June). Mercury: General information. GOV.UK.

Veríssimo, A., Barreto, P., Tarifa, R., & Uhl, C. (1995). Extraction of a high-value natural resource in Amazonia: The case of Mahogany. Forest Ecology and Management, 72(1), 39–60.

Watson, F. (1996). A view from the forest floor: The impact of logging on indigenous peoples in Brazil. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 122(1), 75–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8339.1996.tb02064.x

Wetzler, E. A., Marchesini, P., Villegas, L., & Canavati, S. (2022). Changing transmission dynamics among migrant, indigenous and mining populations in a malaria hotspot in northern Brazil: 2016 to 2020. Malaria Journal, 21(1), 127. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-022-04141-6

WWF. (2006a, March). Logging in the Amazon. https://wwf.panda.org/discover/knowledge_hub/where_we_work/amazon/amazon_threats/oth er_threats/logging_amazon/

WWF. (2006b, June 18). Factsheet: Garimpos – gold mines in the Amazon. https://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?72800%2FFactsheet-Garimpos-Gold-mines-Amazon in-the-Amazon

Zimmerman, B., Peres, C. A., Malcolm, J. R., & Turner, T. (2001). Conservation and development alliances with the Kayapó of south-eastern Amazonia, a tropical forest indigenous people. Environmental Conservation, 28(1), 10–22. doi:10.1017/S0376892901000029

Zimmerman, B. (2013, December 23). Rain forest warriors: How indigenous tribes protect the Amazon. Science. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/131222-amazonkayapo-indigenous-tribes-deforestation-environment-climate-rain-forest –

Leave a comment