In this essay, I will discuss whether women are agents or victims of Fish-for-Sex (FFS) transactions occurring around Lake Victoria. Firstly, I will define FFS and briefly outline key reasons for its occurrence. Then I will discuss how Lake Victoria’s gendered economy, women’s statuses of vulnerability, spread of HIV, declining ecology, and Kenya’s ‘No Sex for Fish’ project demonstrates FFS as a victimising practice. After which, I will discuss how women use FFS as a business strategy, a form of interdependence, and a part of socio-cultural practices. Finally, I will conclude with my thoughts on the overall agentive or victimising state of FFS on women.

Context: Fish-for-Sex & Lake Victoria

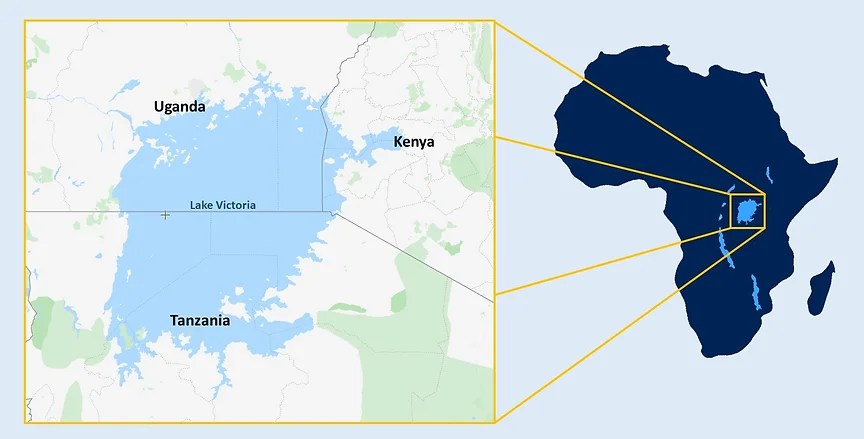

Lake Victoria lies within three countries in sub-Saharan Africa: Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda; it is Africa’s largest freshwater lake and the 2nd largest lake in the world (WWF, 2012). Approximately 40 million people depend on Lake Victoria’s economy and around a third of the total population of its bordering countries rely on the lake for uses such as food, transportation, irrigation etc. (Muyodi, Bugenyiand, and Hecky, 2010). Nile Perch were introduced into Lake Victoria in the 1950s led to the eradication of around 300 species (Barel et al. 1985); despite the growth of global exportation of Nile Perch, lower-value predated fish are inherently important to local people (Geheb, 2008; Medard, 2012). However, in recent years, Nile Perch catches have dramatically decreased (Lake Victoria’s Fisheries Organisation, 2008, cited in Medard, 2012). Lake Victoria has also experienced ecological degradation which has further depleted fish stocks (Mojola, 2011).This has led to higher prices and increased competition among fish traders.

Due to poverty resulting in a lack of funds to buy fish, women fish traders often must agree to transactional sex in exchange (Bene and Merton, 2008). Bene and Merton (2008, p.875) define Fish-for-Sex (FFS) as “particular arrangements between female fish traders and fishermen, in which the fish traders engage in sexual relationships with the male fishers to secure their supply of fish, which they then process and sell to support their families”. FFS happens predominantly in inland fisheries in Sub-Saharan Africa, although it has been observed in developing communities throughout the African continent and an individual case in Papua New Guinea (Bene and Merton, 2008). However, financial insecurity oversimplifies FFS relationships and fails to account for significant socio-cultural dynamics. Below, I will discuss whether FFS in Lake Victoria is an empowering agentive strategy or a victimising practice.

Victims

Gendered Economy

Mojola (2011) explains that gendered economies, where ‘men’s work’ earns more than ‘women’s work’, can result in an economy of transactional sex. In Lake Victoria, transactional sex in exchange for gifts or money is prevalent. Camlin, Kwena, and Dworkin (2013) found that, within Kenyan fishing villages, women were mainly involved in post-harvest activities such as trading, gleaning, processing, and cooking. Women also worked as hoteliers, cooks onboard fishing vessels, and fish brokers to female traders and for small sales. Alternatively, Men were mainly involved in fishing, with some brokering to export companies or large restaurants. Similar employment structures are found in both Uganda and Tanzania (Mandanda, 2003, cited in Geheb et al., 2008; Medard et al., 2019).

Mitchel (1974, cited in Medard et al., 2019) suggests that gendered economies result in gender inequalities and a minority holding significant power over others. They explain that whilst women must rely on weak broker networks and compete against each other, men can act as both fisherman and brokers which provides them with considerable control over fishery activities (Medard et al., 2019). For example, in Tanzania, women hold few roles within fishery governing bodies and their capital networks are limited. Medard (2015) explains that recent increases in global fish exports from Lake Victoria has resulted in many high-risk job opportunities with little alternative livelihood options for men and women. Accessing the fishing community is increasingly difficult and entering through transactional sex (for women) is common. Therefore, the gendered structure of the economy makes women victims of FFS due to their subordinate position in the fishery’s society.

Sometimes fishermen maycoerce women into sex through refusal of fish (Bene and Merton, 2008). As the competition between fish traders is high, which can result in long waiting periods when the catch is low, and FFS often results in securing fish, women may agree to coerced transactional sex. Therefore, women sometimes must engage in FFS just to secure a living.

Vulnerable Individuals

Due to poverty, women fish traders may lack financial funds to purchase fish and often must agree to transactional sex for them in exchange (Bene and Merton, 2008) Women engaging in FFS are often economically or socially vulnerable being mostly migrants, divorcees, household domestic workers, women who have fled political or domestic violence, sex workers, and market-based traders (Camlin, Kwena, and Dworkin, 2013). These individuals are often low on financial funds and find the fish trade an attractive business.

Start-up fish trading is relatively cheap, requires little education or prior skill set, and provides a decent wage. Additionally, fish demand is always high, and unsold fish can be used to feed children. In Kenya, migrant women are the predominate participants in FFS or Jaboya. It is often a necessity to join the Jaboya economy when women have little money to pay brokers additional payments or no prior fishing connections. Therefore, FFS exploits vulnerable women who are seeking access to the fishery economy whose social or economic positions make refusal difficult.

Additionally, vulnerable individuals are the most stigmatized within Lake Victoria’s communities. Camlin, Kwena, and Dworkin (2013) noted that women were less inclined than men to talk about their dealings in FFS (due to social stigma) but will depict woman as victims of the system with little alternative choices. An interviewee commented that women within the fish trade consider FFS to be a significant pitfall of their work. FFS transactions are often blamed on women as traders offer transactional sex to gain a steady fish supply in times of fierce competition with stock shortages. Therefore, FFS victimises women by stigmatising them which makes it less likely that women would choose it an agentive strategy.

Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs)

FFS is often considered a form of prostitution which is causing STDs to spread which women are often blamed for (Bene and Merton, 2008). Widespread transactional sex results in the gift receiver having multiple partners (a risk factor for HIV) and being unable to negotiate safe sex (Mojola, 2011). Go et al. (2003 cited in Nathenson et al., 2017) states that women’s sexual safety is often determined by her social and economic security, which is determined by her husband occupational status. HIV/AIDs is the primary cause of adult deaths in sub-Saharan Africa which is also the STD’s global hotspot. Allison and Seeley (2004) state that women are at a higher risk of HIV in fisheries due to their subordinate community position. Fiorella et al. (2015) found that HIV risk increased with short-term fish declines although she argued that long-term decline could decrease HIV cases. This demonstrates that some women knowingly increase their HIV risk by participating in FFS transactions due to gender inequalities preventing fair trade, thus FFS can be viewed as a victimising practice.

Declining Ecology

Despite the possibility of a cultural basis of FFS transactions, some scholars argue that the practice is relatively new (Bene and Merton, 2008). Mojola (2011) argues that environmental and economic decline are both contributing factors to FFS. Interviewees expressed that Lake Victoria has become polluted in recent years due to eutrophication with sewage contamination, run-off from agricultural fertilisers, and nearby deforestation causing erosion. Another cause of the environmental decline was the increased reliance on Lake Victoria following Kenya’s job market shrinkage in the 1980s. Consequently, in recent years, fish populations have declined due to the growth of aquatic weeds; this has led to fish breeding being destroyed which caused a decline in the number of fish caught. Geheb and Binns (1997) discuss that economic decline has led more people to turn to fishing which, coupled with the decline in caught fish, has led to increased competition between fish traders. These ecological changes alongside the gendered economy increased instances of FFS by putting women in increasingly competitive positions (Camlin, Kwena, and Dworkin, 2013).

Empowerment

In Kenya, a ‘No Sex for Fish’ project aimed to reduce the incidences of FFS by empowering women through the creation a women’s cooperative village saving scheme (Nathenson et al., 2017). Funds raised from this were used to provide fishing vessels, business skills training and increase wages. These provisions decreased women’s dependency on men for an income and increased their control over catch distribution. The project aimed to change gendered attitudes and reduce power imbalances within the gendered economy. A key aspect of the project was changing the gender hierarchy by having men employed under women; this has resulted in men showing more respect towards women and entertaining business partnerships which do not involveFFS.

The project has resulted in an increase in income for the female boat owners which was used to mend houses and send children to school (Nathenson et al., 2017). Several women stated that they felt empowered and less reliant on FFSrelationships as the men must negotiate with them as managers; additionally, they now had places on the Beach Management Unit and other institutions which provides them with a community voice. Overall, the project has resulted in decreased instances of FFS which demonstrates that women were engaging in transactional sex more out of necessity than for use as an agentive business strategy.

Agents

Business Strategy

Camlin, Kwena, and Dworkin (2013) argue that women are also agents of FFS. This perspective is prevented by not accounting for women’s active roles within the fishery, comparing the FFS system to prostitution, and stigmatisation surrounding STD transmission and poverty. Female fish traders are excellent businesswomen being highly mobile, in order to be present when fish are brought in at different beaches, and use their mobile phones to track market prices and boat locations. Bene and Merton (2008) argue that women employ FFS as a business strategy when fish supplies are uncertain. Markets for consumption are not well connected to inland fisheries in Sub-Saharan Africa, which, alongside highly mobile fishers with fluctuating catches, makes transaction costs high when looking for fish. Thus, FFS makes purchasing fish cheaper and a form of business strategy,

Moreover, women traders were more able to become fish brokers if they engaged in FFS relationships, therefore they would engage in it to gain this economic advantage (Camlin, Kwena, and Dworkin, 2013).

Women also expressed that their business relationships felt more reliable once consolidated with sex (Rajabu, 2012, cited in Medard et al., 2019). Therefore, some women actively seek FFS transactions as they feel it gives their family more financial security. In fact, some women earn enough to own their own boats and in rare cases some of these women supposedly ask for FFS from traders.

Furthermore, there exists a social hierarchy among women traders related to fish access. Those with a lack of business networks, and thus no sustained fish access, are of a low status; women who have secure fish access, due to FFS transactions or through marriage, are of higher status (Camlin, Kwena, and Dworkin, 2013). Therefore, women may seek FFS transactions to elevate their social status.

Interdependence

Another aspect of FFS relationships is the interdependence garnered between fish traders and fisherman (Camlin, Kwena, and Dworkin, 2013). Traders (specifically women involved in FFS relationships) provide support to fishermenin times of fish scarcity which can be in the form of financial support, providing food, or service provision such as purchasing or repairing fishing equipment. One woman stated that these services created a relationship that made it unlikely the fishermen would sell elsewhere. This independence also raises a women’s status from an individual engaging in transactional sex to a family-like figure for the fishermen. Thus, forming interdependent FFS relationships can be an effective strategy at avoiding community disapproval whilst gaining assured fish access.

Socio-cultural Practices

Bene and Merton (2008) argue that explaining FFS’s occurrence due to financial insecurity, or fish decline is too simplistic as FFS is documented predominantly in sub-Saharan Africa and therefore is likely related to socio-cultural practices. The main ethnic groups living on Lake Victoria’s perimeter include the Luo in Kenya, the Sukuma in Tanzania, and the Baganda in Uganda (Geheb et al., 2000:49; Wilson, 1996, cited in Medard, 2015).

The Luo live in Nyanza province and are third largest ethnic group in Kenya (Mojola, 2011). During the 1980s, the province experienced a reduction in work opportunities, resulting in many Luo entering the more reliable fish trade. In Luo culture, widows must remove impurities of death by having unprotected sex with a ‘cleanser’ whilst couples and widows are expected to engage in unprotected sex after specific community events. Access to fish in Nyanza is given to women engaged in sexual relations with fisherman either through marriage or extramarital relations (Mojola, 2011), which may be a result of Luo traditions.

In Mwanza, Tanzania, many women expressed that receiving gifts from men was a requirement for sex and not receiving a gift was a sign of disrespect (Wamoyi et al., 2010). The Sukuma practice polygamy and allow divorce; they brought these practices with them to Lake Victoria (Medard, 2015). Medard (2012) explained that divorced women often become driers in dagaa fisheries where there is an expectation for women to exchange sex. However, the women expressed there was no shame in the practice which is related to their social values.

Similarly, Girls in Southern Uganda request money to pay for necessities in return for sex although many expressed not exchanging sex for gifts would be disrespectful even with financial stability (Wamoyi et al., 2010). These examples demonstrate that transactional sex in Uganda, Tanzania, and Kenya is not always motivated out of economic means but from cultural ideologies. Thus, women can be agents of transactional sex like FFS, seeking such relationships to abide by social norms.

Conclusion

Despite the agentive argument above, I conclude that FFS is a mostly victimising practice entrenched in socio-cultural norms which has increased in recent years by ecological decline and the gendered economy. Women’s views on FFS vary from expressing they have little choice due to gendered power dynamics to stating FFS holds no shame (Camlin, Kwena, and Dworkin, 2013; Medard, 2012). Overall, women are put at a disadvantage within the fish trade’s high-risk, competitive industry, so they may seek FFS relationships to gain advantages.

Fiorella et a., (2015) have stressed that for FFS to decrease there needs to be more opportunities for women to enter managerial roles as well as preventing overharvesting in Lake Victoria. The success of Kenya’s ‘No Sex for Fish’ project (Nathenson et al., 2017), will hopefully lead to similar projects in Uganda and Tanzania. Further research could look at Lake Victoria’s tourism (Outa, 2020), and its effect of FFS practices.

References

Allison, E. H. and Seeley, J. A. (2004) ‘HIV and AIDS among fisherfolk: A threat to ‘responsible fisheries’?’, Fish and Fisheries, 5(3), pp. 215–234. Available at: doi:10.1111/j.1467-2679.2004.00153.x.

Barel, C., Dorit, R., Greenwood, P., Fryer, G., Hughes, N., Jackson, P., Kawanabe, H., Lowe-McConnell, R., et al. (1985) ‘Destruction of fisheries in Africa’s Lakes’, Nature, 315(6014), pp. 19–20. Available at: doi:10.1038/315019a0.

Béné, C. and Merten, S. (2008) ‘Women and fish-for-sex: Transactional sex, HIV/AIDS and gender in african fisheries’, World Development, 36(5), pp. 875–899. Available at: doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.05.010.

Camlin, C.S., Kwena, Z.A. and Dworkin, S.L. (2013) ‘jaboyavs.jakambi: Status, negotiation, and HIV risks among female migrants in the “sex for fish” economy in Nyanza Province, Kenya’, AIDS Education and Prevention, 25(3), pp. 216–231. Available at: doi:10.1521/aeap.2013.25.3.216.

Fiorella, K.J., Camlin C.S, Salmen C.R., Omondi, R, Hickey, M.D, Omollo, D.O., Milner, E.M, Bukusi, E.A., et al. (2015) ‘Transactional fish-for-sex relationships amid declining fish access in Kenya’, World Development, 74, pp. 323–332. Available at: doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.05.015.

Geheb, K. and Binns, T. (1997) ‘“fishing farmers” or “farming fishermen”? the quest for household income and nutritional security on the Kenyan shores of Lake Victoria’, African Affairs, 96(382), pp. 73–93. Available at: doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a007822.

Geheb, K., Kalloch, S., Medard, M., Nyapendi, A., Lwenya, C., Kyangwa, M. (2008) ‘Nile perch and the hungry of lake victoria: Gender, status and food in an East African fishery’, Food Policy, 33(1), pp. 85–98. Available at: doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2007.06.001.

Medard, M. (2012) ‘Relations between people, relations about things: Gendered investment and the case of the Lake Victoria Fishery, Tanzania’, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 37(3), pp. 555–566. Available at: doi:10.1086/662704.

Medard, M. (2015). A Social Analysis of Contested Fishing Practices in Lake Victoria. Ph. D. Thesis. Wageningen University. Available at: https://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/wurpubs/486862 (Accessed: 10 Jan 2024)

Medard, M., van Dijk, H. and Hebinck, P. (2019) ‘Competing for kayabo: Gendered struggles for fish and livelihood on the shore of Lake Victoria’, Maritime Studies, 18(3), pp. 321–333. doi:10.1007/s40152-019-00146-1.

Mojola, S.A. (2011) ‘Fishing in dangerous waters: Ecology, gender and economy in HIV risk’, Social Science & Medicine, 72(2), pp. 149–156. Available at: doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.11.006.

Muyodi, F.J., Bugenyi, F.W. and Hecky, R.E. (2010) ‘Experiences and lessons learned from interventions in the Lake Victoria Basin: The Lake Victoria Environmental Management Project’, Lakes & Reservoirs: Science, Policy and Management for Sustainable Use, 15(2), pp. 77–88. Available at: doi:10.1111/j.1440-1770.2010.00425.x.

Nathenson, P., Slater, S., Higdon, P., Aldinger, C. and Ostheimer, E. (2016) ‘No sex for fish: Empowering women to promote health and economic opportunity in a localized place in Kenya’, Health Promotion International [Preprint]. Available at: doi:10.1093/heapro/daw012.

Outa, N., Yongo, E., Keyombe, J., Ogello, E., Wanjala, D. (2020) ‘A review on the status of some major fish species in Lake Victoria and possible conservation strategies’, Lakes & Reservoirs: Science, Policy and Management for Sustainable Use, 25(1), pp. 105–111. Available at: doi:10.1111/lre.12299.

Wamoyi, J.,Wight, D., Plummer, M., Mshana, G.H., and Ross, D. (2010) ‘Transactional sex amongst young people in rural northern Tanzania: An ethnography of young women’s motivations and negotiation’, Reproductive Health, 7(1). Available at: doi:10.1186/1742-4755-7-2.

WWF (2012) Great rift lakes of Africa, WWF. Available at: https://wwf.panda.org/discover/knowledge_hub/where_we_work/africa_rift_lakes/ (Accessed: 10 January 2024).

Leave a comment